Michelangelo 's four nail Crucifix : Rediscovery of the bronze model documented by Francisco Pacheco , Seville 1597

By Carlos Herrero Starkie

Download PDF

In his book “The Art of Painting, “Pacheco mentions on three occasions explicitly a bronze Crucified Christ with four nails attributed to Michelangelo, which the silversmith Juan Bautista Franconio brought from Rome to Seville in the year 1597, inspiring Juan Martínez Montañés design of the Christ of the Chalices in 1603.

This Crucifix is known from an image that was incorporated into Velázquez’s portrait of Sor Jerónima de la Fuente in 1620 and from five casts made by Juan Bautista Franconio directly from this bronze model, all of them considered the Spanish first generation series: in bronze, the Crucified Christ on the Cross polychromed by Pacheco the 17th January 1600, currently in the Ducal Palace of Gandía, and another one, also polychromed located in Italy, belonging to a private collection; in silver, the Christ Crucified with four nails, in the Cathedral of Seville, the one in the Royal Palace (Madrid) of similar quality, and the Crucifix in the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation (Granada), former Manuel Gómez Moreno Collection all cast around 1600.

The purpose of this study is to introduce this bronze Crucified Christ attributed to Michelangelo, which was long thought lost and whose information was provided by Pacheco himself when he indicated that, after serving as a model for artists and sculptors, Juan Bautista Franconio gave it to Father Pablo Céspedes, who cherished it and wore it around his neck until his death in 1608.

Read more

Download PDF

In his book “The Art of Painting, “Pacheco mentions on three occasions explicitly a bronze Crucified Christ with four nails attributed to Michelangelo, which the silversmith Juan Bautista Franconio brought from Rome to Seville in the year 1597, inspiring Juan Martínez Montañés design of the Christ of the Chalices in 1603.

This Crucifix is known from an image that was incorporated into Velázquez’s portrait of Sor Jerónima de la Fuente in 1620 and from five casts made by Juan Bautista Franconio directly from this bronze model, all of them considered the Spanish first generation series: in bronze, the Crucified Christ on the Cross polychromed by Pacheco the 17th January 1600, currently in the Ducal Palace of Gandía, and another one, also polychromed located in Italy, belonging to a private collection; in silver, the Christ Crucified with four nails, in the Cathedral of Seville, the one in the Royal Palace (Madrid) of similar quality, and the Crucifix in the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation (Granada), former Manuel Gómez Moreno Collection all cast around 1600.

The purpose of this study is to introduce this bronze Crucified Christ attributed to Michelangelo, which was long thought lost and whose information was provided by Pacheco himself when he indicated that, after serving as a model for artists and sculptors, Juan Bautista Franconio gave it to Father Pablo Céspedes, who cherished it and wore it around his neck until his death in 1608.

Read more

Michelangelo's involvement in the four-nails Crucifix model and Vittoria Colonna

By Carlos Herrero Starkie

Download paper

The author presents a meticulous analysis of Michelangelo's involvement in the recently rediscovered bronze model of the Four-Nailed Crucified Christ, documented by Francisco Pacheco in Seville in 1597. He upholds the thesis that Michelangelo not only conceived the design—as evidenced by the preparatory drawings in the Teylers Museum and the “Four Crosses” drawing in the British Museum, both unanimously attributed to the artist—but that he also personally fashioned the wax model, which he gave to Vittoria Colonna between 1538 and 1541, within the context of a spiritually intense relationship.

Herrero Starkie, after quoting Condivi and Varchi references to a naked Crucifix given to Vittoria Colonna and surveying the full critical reception of this Crucified Christ model—citing the contributions of scholars such as Gómez Moreno (1930), Phillips Goldsmith (1937), Tolnay (1978), Marino (1992), Shell (1992), and more recently, Bambach (2017), Bosh (2018), Joannides (2022), and Riddick—offers a personal yet rigorously substantiated interpretation of three letters exchanged between the Marchesa of Pescara and Michelangelo. These letters concern a small Crucifix described by Colonna as perfect in itself, though still incomplete as part of a larger project, and one which invites scrutiny under light, magnifying glass, and mirror—elements that underscore the three-dimensional character of the “cosa” in question.

In doing so, the author distances himself from the prevailing Anglo-Saxon scholarly tradition, which has generally interpreted these letters as referring to a drawing—specifically, the “Living Christ” drawing in the British Museum. Instead, he lends further support to the view, most notably advocated by Michael Riddick, that the object in question was in fact a wax model of a Crucifix. This argument is founded, on the one hand, on the tone and meaning of the language of the letters, which imply a distinction between the finely modeled object temporarily in Colonna's possession and a larger, as-yet-unrealized work; and on the other, on Colonna’s expressed uncertainty as to whether it would be Michelangelo himself or one of his assistants who would eventually execute the final piece—an uncertainty that fuels her concern that the finished work might never attain the perfection of the model, a notion wholly consistent with the complex challenges of the casting process.

The text concludes with a search for stylistic correspondences between this model of the dead Christ— naked, with bowed head and crossed legs—and other works by the Master, such as the Crucified Christ of the Church of Santo Spirito, the collapsed Christ in the lap of the Virgin in the Vatican Pietà, and the David. Through these comparisons, the author demonstrates that the Four-Nailed Christ model, aside from conveying profound spiritual emotion, clearly belongs within the canon of Michelangelesque masculine beauty. This is evidenced in the expressive face, which captures the liberating instant of death, and in the body, whose musculature is rendered with scientific precision, resulting in a symmetrical and restrained composition: a plastic representation of the final breath of Renaissance.

Read more

Download paper

The author presents a meticulous analysis of Michelangelo's involvement in the recently rediscovered bronze model of the Four-Nailed Crucified Christ, documented by Francisco Pacheco in Seville in 1597. He upholds the thesis that Michelangelo not only conceived the design—as evidenced by the preparatory drawings in the Teylers Museum and the “Four Crosses” drawing in the British Museum, both unanimously attributed to the artist—but that he also personally fashioned the wax model, which he gave to Vittoria Colonna between 1538 and 1541, within the context of a spiritually intense relationship.

Herrero Starkie, after quoting Condivi and Varchi references to a naked Crucifix given to Vittoria Colonna and surveying the full critical reception of this Crucified Christ model—citing the contributions of scholars such as Gómez Moreno (1930), Phillips Goldsmith (1937), Tolnay (1978), Marino (1992), Shell (1992), and more recently, Bambach (2017), Bosh (2018), Joannides (2022), and Riddick—offers a personal yet rigorously substantiated interpretation of three letters exchanged between the Marchesa of Pescara and Michelangelo. These letters concern a small Crucifix described by Colonna as perfect in itself, though still incomplete as part of a larger project, and one which invites scrutiny under light, magnifying glass, and mirror—elements that underscore the three-dimensional character of the “cosa” in question.

In doing so, the author distances himself from the prevailing Anglo-Saxon scholarly tradition, which has generally interpreted these letters as referring to a drawing—specifically, the “Living Christ” drawing in the British Museum. Instead, he lends further support to the view, most notably advocated by Michael Riddick, that the object in question was in fact a wax model of a Crucifix. This argument is founded, on the one hand, on the tone and meaning of the language of the letters, which imply a distinction between the finely modeled object temporarily in Colonna's possession and a larger, as-yet-unrealized work; and on the other, on Colonna’s expressed uncertainty as to whether it would be Michelangelo himself or one of his assistants who would eventually execute the final piece—an uncertainty that fuels her concern that the finished work might never attain the perfection of the model, a notion wholly consistent with the complex challenges of the casting process.

The text concludes with a search for stylistic correspondences between this model of the dead Christ— naked, with bowed head and crossed legs—and other works by the Master, such as the Crucified Christ of the Church of Santo Spirito, the collapsed Christ in the lap of the Virgin in the Vatican Pietà, and the David. Through these comparisons, the author demonstrates that the Four-Nailed Christ model, aside from conveying profound spiritual emotion, clearly belongs within the canon of Michelangelesque masculine beauty. This is evidenced in the expressive face, which captures the liberating instant of death, and in the body, whose musculature is rendered with scientific precision, resulting in a symmetrical and restrained composition: a plastic representation of the final breath of Renaissance.

Read more

Michangelo 's Crucifix for Vittoria Collonna and the rediscovery of a Crucifix by Michelangelo brought to Spain by Juan Bautista Franconio

Tefaf Maastrich 2025 Michelangelo + Velázquez

Download PDF

Download Stuart Lochhead paper, Michelangelo +,Velazquez

It is with profound honour that we present at our stand at TEFAF the rediscovered bronze Corpus Christi, the finest extant example of Michelangelo’s extraordinary four-nails Crucifix design. This masterpiece, so intimate in scale yet monumental in its impact, holds a unique place in the story of Italian Renaissance art’s global diffusion. Displayed alongside Velázquez’s Sor Jerónima de la Fuente, where this very image of Christ is rendered in painted form, the dialogue between these two works offers a rare opportunity to consider Michelangelo’s influence across time, media, and geography.

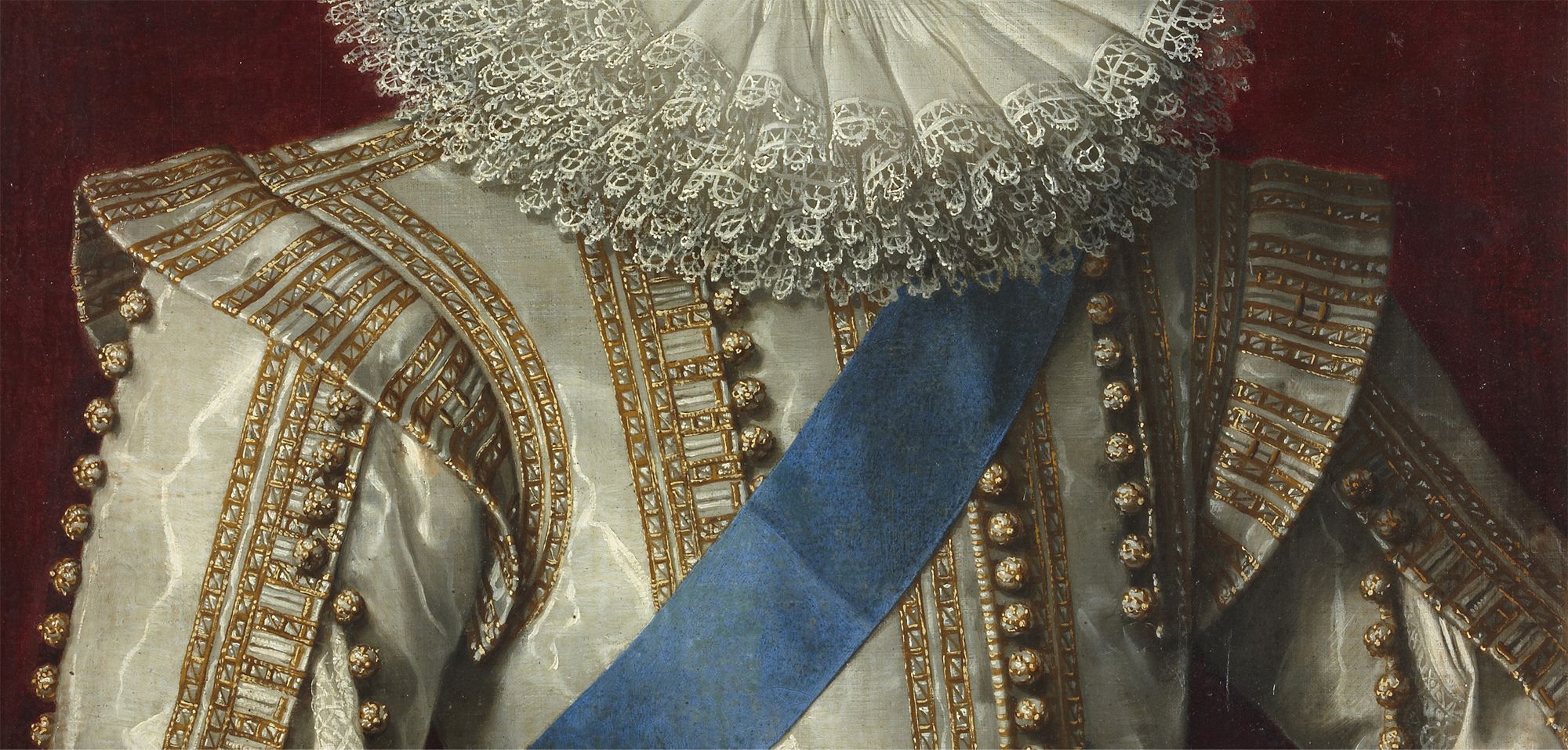

The tale of this remarkable design is as compelling as the object itself. Created in the early sixteenth century, the Crucifix journeyed from Italy to Seville in 1597, finding its way into a vibrant artistic and spiritual milieu. From Seville—a gateway to the New World—it transformed not only local devotions but also the image of the Crucified Christ across the ocean. The four-nailed configuration, a departure from the traditional three-nail representation, accentuates the physical suffering of Christ while preserving a balance of pathos and serenity. This duality resonates powerfully with the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on personal piety and the theological depth of Christ’s sacrifice. The bronze’s astonishing craftsmanship testifies to the outstanding achievements in the art of casting in Rome towards the end of the sixteenth century. Every detail, from the tension of Christ’s musculature to the sublime stillness of his expression, is rendered with minute precision, elevating the work beyond mere technical achievement. Its feather weight is further proof of the consummate skill employed in casting.

We are thrilled to share this masterpiece with you at TEFAF. The discovery and presentation of this bronze serve as a poignant reminder of the enduring relevance of Michelangelo’s legacy. The Corpus and Velázquez’s Sor Jerónima, brought together here for the first time, invite us to reflect on the profound dialogues between artists across chronologies and geographies.

Stuart Lochhead

Read More

Download Stuart Lochhead paper, Michelangelo +,Velazquez

It is with profound honour that we present at our stand at TEFAF the rediscovered bronze Corpus Christi, the finest extant example of Michelangelo’s extraordinary four-nails Crucifix design. This masterpiece, so intimate in scale yet monumental in its impact, holds a unique place in the story of Italian Renaissance art’s global diffusion. Displayed alongside Velázquez’s Sor Jerónima de la Fuente, where this very image of Christ is rendered in painted form, the dialogue between these two works offers a rare opportunity to consider Michelangelo’s influence across time, media, and geography.

The tale of this remarkable design is as compelling as the object itself. Created in the early sixteenth century, the Crucifix journeyed from Italy to Seville in 1597, finding its way into a vibrant artistic and spiritual milieu. From Seville—a gateway to the New World—it transformed not only local devotions but also the image of the Crucified Christ across the ocean. The four-nailed configuration, a departure from the traditional three-nail representation, accentuates the physical suffering of Christ while preserving a balance of pathos and serenity. This duality resonates powerfully with the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on personal piety and the theological depth of Christ’s sacrifice. The bronze’s astonishing craftsmanship testifies to the outstanding achievements in the art of casting in Rome towards the end of the sixteenth century. Every detail, from the tension of Christ’s musculature to the sublime stillness of his expression, is rendered with minute precision, elevating the work beyond mere technical achievement. Its feather weight is further proof of the consummate skill employed in casting.

We are thrilled to share this masterpiece with you at TEFAF. The discovery and presentation of this bronze serve as a poignant reminder of the enduring relevance of Michelangelo’s legacy. The Corpus and Velázquez’s Sor Jerónima, brought together here for the first time, invite us to reflect on the profound dialogues between artists across chronologies and geographies.

Stuart Lochhead

Read More

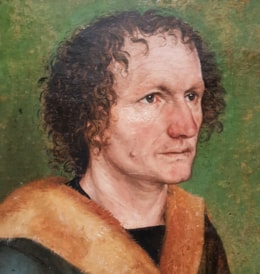

Tribute to the modeletto of the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi by Van Dyck

Carlos Herrero Starkie

Director of IOMR

April 2024

Download comparative study with images

It was on the occasion of the cataloguing of several works from the collection of the Marquess of Bristol at Ickworth House, when in 1963 Michael Jaffé, director of the Fitzwilliam Museum and professor of Western Art at Cambridge University, was captivated by the magnetism emanating from this ravishingly modeletto of a young Genoese woman traditionally considered as the Marchesa Balbi (Fig 1), assigning it, due to its vibrant execution and compelling gaze, to the talented hand of the prodigious painter, Anthony van Dyck, a work from his Genoese period. Years later, he identified the sitter as Ottavia Balbi, by relating it to the magnificent full-length portrait of the Marchesa Balbi, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Fig. 2), and to a sketch listed in the catalogue of drawings of the Devonshire Collection 2002 p. 71 (1).

In light of this discovery, Susan Barnes, the most respected authority on the study of Van Dyck in Genoa, confirmed its autograph nature, considering it as a paradigmatic example of the particular way the Master portrayed from life and alla prima the Genoese nobility in their palaces. Therefore in 2004 she included this modeletto as an autograph work in the catalogue raisonné of the artist (2).

In 1996, David Jaffé, curator of European paintings at the Getty Museum, confirmed its attribution to Van Dyck on the occasion of Sotheby's auction "The east Wing Ickworth House" 1996, in his failed attempt to acquire the work for the Getty Museum, after a crowded bidding war against my father (3). Shortly afterwards, we lent the work for the exhibition Van Dyck - Genoa curated in July 1997 by Piero Boccardo and Susan Barnes, exhibited at the Palazzo Ducale alongside one of its only pairs, the modeletto of the Marchesa Grimaldi Cattaneo (Fig. 3), and in harmony with the magnificent full-length portrait of the Marchesa Balbi (Fig. 2), which strongly recalls the portrait of Maria Serra Pallavicino by Rubens (Fig. 5) (4). Apart from Susan Barnes, who honoured us with her presence many times, among the many scholars and curators who saw the work in my House in Madrid, I would highlight Blaise Ducos, curator of Flemish painting at the Louvre, CD Dickerson head of European paintings and sculpture of the National Gallery of Art, Nicola Spinosa, director of the Capodimonte Museum, Micha Leeflang from the Catharijneconvent Museum and our friend, Matías Díaz Padrón, former director of the department of Flemish painting at the Prado Museum and a leading authority in Van Dyck, who, captivated by the charms of this portrait so well enhanced by the hand of Van Dyck, included it as a reference work in his Catalogue raisonné on Van Dyck's work in Spain (5).

We are therefore facing a magnificent example of Van Dyck's pictorial skills, representing one of the rising stars of Genoese society in the early 17th century, the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, and boasting an impeccable provenance that dates back uninterruptedly since more than two centuries, through the successive owners of the Bristol House, many of whose works, like this modeletto, were acquired during their periodic Grand Tours of Italy and sold centuries later in the Sotheby’s auction of 1996 (6).

As a tribute to this magnificent work, of my collection, I would like to delve into the three axes that make it a piece de résitance of great value in Van Dyck Corpus.

A) The paradigmatic character with which Van Dyck's portraiture genius is expressed in this modeletto.

B) The importance of representing such an iconic member of the Genoese family with stronger economic ties in Antwerp, as the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, who introduced Van Dyck to Genoa in 1621.

C) Its historical provenance from Ickworth House, owned by the Marquesses of Bristol. A family linked to Italy through their periodic Grand Tours.

A) The paradigmatic character with which Van Dyck's portraiture genius is expressed in this modeletto.

"… one could expect an oil sketch of this period to be of the highest quality.” Van Dyck Anatomy of Portraiture, 2016.

This modeletto, by its very nature, highest pictorial quality and pristine state of condition, contains, like none of the few that have survived, the quintessence of Van Dyck's portrait genius, his ability to spontaneously capture the very moment when the painter grasps the soul of the portrayed sitter and translates it onto paper with the freshness, looseness, and brevity of stroke that led him to reach the pinnacle of his Art in Genoa, as the greatest portraitist of the 17th century, a consideration already evident in his self-portrait at the age of just 16 (Fig. 7) and in his youthful masterpiece, the portrait of Cornelisz van der Geest (Fig. 6).

Oil sketches, made ad vivum, attest to a working method, which evolved from 1521 in Genova to 1528 in Antwerp towards the virtuosity of the drawing series and the grisailles for engravings achieved circa 1530/35 (Fig. E) and the rather prosaic oil sketches representing magistrates circa 1534 (Fig. C, Fig. D). This technique persisted in England through preparatory oil studies sketched directly on the original canvas, unfortunately now lost due to being covered by the final images elaborated by Van Dyck and his assistants in the workshop. However, none of these authentic icons of English portraiture, due to the ease, nonchalance, and melancholy of his sitters, retain the immediacy of his youthful effigies or the vivacity of gaze of the most probably lost modeletto representing the portrait of Lucas van Uffel, circa 1623 (Fig. 9), or the compelling presence of the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi’s portrait that we are studying here (Fig. 8) (7).

Only on some occasions does Van Dyck express himself with such confidence and brio as in this modeletto, in which a strong connection with the sitter can be perceived, a mutual magnetism that inspires the Master's intelligence and sensitivity in his process of capturing the psychology of the person in front of him. He does it intuitively, in a process similar to a self-portrait (Fig. 11, 12) that can only be achieved when one knows the model well, like Ottavia, whom he probably met as a child in Antwerp.

All of Van Dyck's representative portraits share a common characteristic empathy with the sitter that allows his genius to emerge, through a technique that anticipates Luca Giordano's fa presto and recalls Frans Hals (Fig. 16). Van Dyck fixes his gaze on this young woman, and in a few moments, his hand already resonates with the sprouts of imagination from which the soul of the Marchesa's effigy emanates allowing him to display the face on paper with just four strokes, seen in three quarters, and transfer that lively, interrogative gaze, in virtual contrapposto that pursues both him and us as we contemplate the work.

This sguardo, both dignified and acute, distant and communicative, typical of Van Dyck, which he perhaps draws from Rubens in his portrait of Brigida Spinola-Doria NGA (Fig 4), is intimately related to the way those magnetic eyes are painted, acting as a touchstone to discover the autograph character of his Genoese work. Van Dyck lightly marks the lower eyelids, a bit more the upper ones, skilfully and boldly delimiting both with a pinkish line and a hint of white; the irises, perhaps one more defined than the other, each show a spot of white, in almost identical and meridian position that fixes the sitter's gaze, giving the eyes that typical moist character of Van Dyck.

The ochre shadows that define the eyebrows, nose, chin, the corners of the lips, and a tremendously expressive mouth, with a slightly sensual gesture, in fine contrast with the striking pink of the cheeks and the stream of luminosity on the forehead, allow us to define the work as rather dramatic, where the interplay of light and shadow, il chiaroscuro, highlights the significantly individualized features of the Marchesa's countenance. An imprint concentrated on her powerful gaze and the subtly provocative expression of her lips, contributing to give a halo of femininity to the work (Fig. 13).

The chestnut imprimatura that stands out from the brown background treated in a very loosely manner, as befits a modeletto, where the somewhat casual hairstyle of the model reveals a bun very characteristic of Genoese fashion, adorned with small pearls, authentic flashes of light, painted with the masterful liveliness and lightness that characterizes the Master, from which hangs a round adornment only sketched, but which could well identify the Marchesa, all this leads us to maintain Susan Barnes' thesis, that places this modeletto in the last Genoese years, at least four years after the National Gallery of Art portrait of the Marchesa Balbi made by Van Dyck surely on the occasion of her marriage to Bartolomeo Balbi, as arranged before his death in 1621 by Gio Agostino Balbi, Ottavia's father. On the contrary, this modeletto could well be related, as Susan Barnes does in her catalogue raisonné, to another later portrait of the Marchesa, of which the portrait in the Denver Museum of Art could be a replica, sold in poor state of condition and which, after being recently acquired by a private collection and carefully restored, has shown to have sufficient quality to be considered a Van Dyck (Fig. 14) (8).

This dazzling modeletto, already excellent for its brevity, immediacy, and ingenuity, would not impact us in the way it does, if it were not for the fact that Van Dyck, in a display of technical virtuosity in its looseness very characteristic of him and other contemporary geniuses such as Velázquez (Fig. 15) and Frans Hals (Fig. 16), dresses the model with a ruff that, due to the lightly, lively, and vivacious way its brocades are rendered, gives the whole an ethereal, almost spectral nature. Something that we also find in the modeletto of the Marchesa Grimaldi Cattaneo (Fig. 10), being a hallmark of these Genoese sketches and especially of some of his last Genoese paintings.

This modeletto (Fig. 13), with its slight tenebrism, only Caravaggesque in how it illuminates the face, although not in its pictorial and lively technique, far removed from the luminous clarity of the portraits of Antwerp, like that of Gaspard Charles van Nieuwenhoven (Fig. 17) of the Phoebus Foundation, but with the same esprit and brio in the brushstroke, can be securely dated to the end of his stay in Genoa around 1627 and would correspond to a portrait of Ottavia when she was about 18 years old, from which the portrait formerly in Denver Museum of Art would also derive, coinciding with the year she becomes Marchesa Balbi upon the death of Gerolamo Balbi, her husband's father, merging the two family lines in her (9).

From this late Genoese period, we can cite as examples, the remarkable portrait of De Wael brothers (Fig. 18) where Van Dyck culminates a delicate chiaroscuro in the treatment of the features to sharpen the rendering of each brother's distinct temperament, the portrait of Porzia Imperiale and her daughter (Fig. 19) Francesca Maria, who displays a similar gaze, both in its angle of vision and intensity, the portrait of the Lomellini family (Fig. 20), where one can perceive in a stellar manner the warlike atmosphere in which Genoa was immersed as a result of the War with Piedmont, which we also observe in the equestrian portraits of Gio Paolo Balbi and Anton Giulio Brignole-Sale, in which Van Dyck combines his typical sprezzatura with an economy of means and efforts that characterizes this period and allows his prodigious artistic genius.

B) The importance of representing a member of the Genoese family with stronger ties in Antwerp, such as the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, who introduced Van Dyck to Genoa.

This modeletto has traditionally been considered by the Bristol House as a portrait of the Marchesa Balbi (Fig. 23). In its upper left side, there is an ancient inscription with the word Balbi, by virtue of which it could be presumed that it was acquired from the Balbi family; whether that inscription was made in Italy or later in England is unknown. Its relation to Ottavia Balbi is first pointed out by Michael Jaffé in 1963 (10).

The Balbi family was very well established in Antwerp at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century, where they opened branches of their textile and banking businesses, to the point that at least three of its members were Consuls of Genoa in Antwerp: Bartolomeo Balbi during the years 1573 and 1592, marrying Lucrezia Santvoort in 1572, Gerolamo Balbi in 1585 and 1592, and Gio Agostino 1610, 11, and 1615 also marrying a citizen of Antwerp, Ines. All of them raised their children in Antwerp, with Gio Agostino being the one who staid longer there, founding the convent of the minorities of Saint Francis of Paul in 1615. He had an illegitimate Flemish child, Ottavia, who by the terms of his testament was obliged to marry a member of the family in order to gained his inheritance. Gio Agostino certainly met young Van Dyck who already in the 1620s had an independent workshop, as attested by the portrait, now disappeared, that Van Dyck made of him, just before his death in 1621 and his departure to Italy (11). It is therefore generally assumed that the Balbi family introduced him to the aristocratic Genoese environment, and it is very likely that he stayed at their Palace in Genoa when he was not lodging at the house of the brothers Lucas and Cornelis Wael. Proof of the importance of this family to Van Dyck is that today there is documentary evidence of nine portraits by Van Dyck related to the Balbi family, and it is believed that he must have painted many others that are not registered as such in the inventories of their palaces (Fig. 1, 2, 14, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 31) (12).

In this sense, adverse historical circumstances for the family, such as the participation of the Marquis, Bartolomeo Balbi (Fig. 26), and his brother Gio Paolo (Fig. 27) in the conspiracy against the Republic in 1649 and their subsequent arrest, led to the inventories of the works of art belonging to the main branch of the Balbi family being probably falsified to avoid being seized, with Bartolomeo himself making an inventory just before his arrest where he includes the properties left in inheritance by his father, Gerolamo, who died in 1527. This would explain the existence of numerous portraits by Van Dyck of members of this branch of the family whose identification of the depicted sitter is not well documented and depends today only on tradition or the palace from which they come, as is the case with the portrait of the Marchesa Balbi of the NGA (Fig. 29) and the modeletto of Ottavia Balbi that we are studying (Fig. 28). In other cases, the portrait, well documented, would have been apparently lost, probably because it was hidden to protect it from the police of the republic, such as the well-known equestrian portrait of the Marquis, Bartolomeo Balbi (Fig. 26), or, in order to avoid its identification by the Genoese authorities, the likeness of the portrayed person was even changed for another member of the family not pursued, as occurred with the equestrian portrait of Gio Paolo (Fig. 27), to which they modified the face to that of Francesco Maria Balbi. This circumstance greatly hinders the documentary tracing of the portraits of the principal line of the Balbi family and makes it necessary to delve deeper into other aspects, such as family tradition, provenance, physiognomy, dress style, or the jewels worn by the personages, to identify the individuals depicted (13).

The case of Marchesa Ottavia Balbi is paradigmatic of this issue insofar as, although there is no documentary evidence to attest to it, we have the certainty, as it makes no sense to presume otherwise, that when Van Dyck arrived in Genoa, he must have portrayed Ottavia, the illegitimate Flemish native daughter of the recently deceased Gio Agostino, his friend and promoter of his trip to Italy, especially considering that, following her father's instructions, she married Bartolomeo, the heir of the Balbi Marquisate belonging to the other family line. Consequently, Ottavia Balbi became the true star of Genoese society at the time, as the result of an accumulation of family wealth and power in this young woman who would become Marchesa Balbi in 1627 upon the death of Gerolamo Balbi, her husband's father (Fig. 28, 29, 31, 33).

Of all the portraits related to the Balbi family, three correspond to the same lady whose countenance is similar to the portrait considered of the Marchesa Balbi at the NGA:

- One of the authentic icons of Genoese painting, the portrait of the Marchesa Balbi painted by Van Dyck in 1623 currently at the National Gallery of Art (Fig. 29), represents Ottavia when she was about 14 years old, as reflected in her rounded and somewhat childlike features, which Van Dyck dignifies with a majestic and rather disproportionate green velvet dress studded with gold brocades, showing her with an artificial and forced air of superiority emphasised by the low point of view of the composition and the way she looks from her height; as if this teenager born in Antwerp, whom he knew as a child, was still not accustomed to this pomp required by her recent rank and that her blood did not run with that haughty nature so characteristic of Genoese society. Something that Van Dyck, did not want to silence, by placing those hands in an artificial manner, with a determined intention to express a certain discomfort. All this in total opposition to the elegance and natural bearing of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo who, in her portrait, also currently at the NGA (Fig. 30), advances nonchalantly in space with the parsimony of a swan, showing with naturalness her origin and aristocratic education. The portrait of the Marchesa Balbi currently at the NGA comes directly from Giacomo Balbi, descendant of the principal line of the Balbi, to which Bartolomeo Balbi, Ottavia's husband, belongs (14).

- The recognition of Ottavia Balbi's physiognomy with the Marchesa Balbi depicted in the NGA portrait allows the same title and name to be given to a lady portrayed by Van Dyck who has the similar facial features (Fig. 31) and, coincidentally, is seated with her hands and body in the same position as in the NGA portrait. She also wears a round ornament near her ear that we also see in other portraits of Ottavia Balbi. The portrait belongs to the current owner by inheritance of the same line of the Balbi as the NGA's portrait, coming from Giacomo Balbi, great-grandson of Francesco Maria Balbi 1619-1704 (15).

- The identification of the woman depicted in the modeletto with Ottavia Balbi (Fig. 32) gained public resonance due to the firm opinion maintained for years by Michael Jaffé, on the occasion of its presentation at the Sotheby's auction "The East Wing Ickworth, Suffolk" in 1996. An opinion that he posthumously publishes along with a photo of the work in the catalogue of drawings of the Devonshire Collection Volume I, linking it to the portrait of the Marchesa Balbi at the National Gallery of Art and with a sketch preserved in the Uppsala University Library n21. Furthermore, this opinion was supported with regards the identification of the personage of the full-length portrait of the Marchesa Balbi by the public research undertaken by Boccardo and Magnani published in 1987 on the patronage and collecting of the Balbi.

This thesis is openly questioned by Susan Barnes, on the basis that both paintings were not included in the 1647/49 inventory made by Bartolomeo and no other document attest this hypothesis. While enthusiastically maintaining the autograph character of the modeletto to Van Dyck, she still had doubts regarding the identification of the personage as Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, since the portrayed being somewhat older in the modeletto than in the NGA painting and the pictorial diction and warmer colour palette of the former correspond more to the later period of Genoese van Dyck 1626/27. The meeting point of both theses could be found in considering the small portrait made alla prima as the modeletto of another portrait of Ottavia on the occasion of becoming Marchesa in 1627, whose not entirely fortunate replica would be the portrait of a lady formerly in the Denver Museum of Art (Fig. 33). The sobriety and black colour of the dress worn by Ottavia in this portrait could show mourning for the death of her father-in-law, Gerolamo and would provide another favorable datum for the identification of this lady as Marchesa Ottavia Balbi (16).

C) Its historical provenance from Ickworth House, owned by the Marquesses of Bristol. A family linked to Italy by their periodic "Grand Tours".

Ickworth House (Fig. 35), the Palace that housed the modeletto for over two centuries, is one of the most extraordinary and unusual English palaces. It was conceived and partially built by Lord Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol, Bishop of Derry (1730-1803) (Fig. 36), an Art enthusiast who, as a seasoned traveller, was the protagonist of several "Grand Tours" to Italy, amassing one of the most important collections of paintings, sculptures, and art objects of his time, which unfortunately was partly lost due to looting of his warehouse in Rome in 1798 by Napoleon's troops, with only a few works surviving, including several by Van Dyck, a portrait of Balthasar Carlos by Velázquez (Fig. 37), a great portrait of man by Titian (Fig. 38), and a spectacular fireplace by Canova that adorned the drawing room of Ickworth House (Fig. 39). As one of the largest landowners in Ireland, he maintained several palaces there, conceived more as museums to house his artworks than as living residences. He commissioned the design of Ickworth House to the Italian architect Mario Asprucci the Younger, designer of the gardens of the Palazzo Borghese, conceiving the building as a central rotunda, reminiscent of the Roman Pantheon, flanked by two wings that would serve as galleries (Fig. 35). The IV Earl of Bristol died in Italy in 1803 without seeing the completion of the Palace, which was finished by his son, the first Marquess of Bristol, Lord Frederick Hervey (1769-1859).

The modeletto appears in all the archives and inventories known of the artworks of Ickworth House, from the first one, Seguier 1819 n76, in which it is attributed to Rubens, to the inventory of 1952 where it is already assigned to Van Dyck, being the subject of a letter dated 1963 from Michael Jaffé to the Marquess of Bristol confirming its autograph nature by Van Dyck, followed by an article of his in 1965 in which he confirms this thesis by relating it to the Marchesa Balbi. The work could have been acquired by Frederick (1730-1803), 4th Earl of Bristol, on one of his trips to Italy or by his brother Augustus John Hervey (1724-1779) III earl of Bristol, for whom there is reliable evidence that he was in Genoa in 1752 (17).

NOTES

1. Letter from Michael Jaffé to the Marquess of Bristol stating that this modeletto representing a Genovese woman is an autograph work by Van Dyck dated 1963.

Michael Jaffé. "Van Dyck portraits in De Young Museum and elsewhere" in Art Quarterly vol 28, 1965 p44 n 31.

Michael Jaffé. "The Devonshire Collection of Northern European Drawings" Volume 1 Van Dyck - Rubens pag 71 Umberto Allemandi & co 2002. With image of the modeletto representing Ottavia Balbi, private collection and image of the drawing by Van Dyck representing a study of trials for portraiture, pen and wash Upsala, University library.

2. Susan Barnes" Van Dyck in Italy". PHD dissertation. New York University 1986 NC18.

Susan J Barnes, Nora Poorter, Oliver Millar, Host Vey. "Van Dyck. A complete Catalogue of the paintings". Yale University 2004, pag 233 cat n II. 112 reproduced as Van Dyck.

Susan J Barnes letter to my father indicating the modeletto is an autograph work by Van Dyck 1996.

3. The East Wing Ickworth Suffolk Sotheby’s sale 11 and 12 June 1996 484 acquired by my father. One year later I privately acquired the painting to my father.

4. Catalogue of the exhibition. "Van Dyck. Grande pittura e colezionismo. A Genova". Susan Barnes, Piero Boccardo, Clario Di Fabio, Laura Tagliaferro. Palazzo Ducale, Genova. Comune di Genova. Cat47 pag 232 image 233 Catalogue entry Susan J Barnes. Electa 1997.

Though I was informed by Sotheby’s the night before the sale that several very strong clients would be bidding at the phone, I only had the certitude that the Getty Museum had bided against my father, when in 2012, I met David Jaffé, in those days having left the Getty and working as an independent art historian, visiting a preview at Christies. During the conversation I show him an image of the modeletto, searching his Van Dyck expert opinion. He immediately answers me "you've got it", confirming that the Getty Museum failed to acquire this modeletto representing the Marchesa Balbi at Ickworth sale.

5. Matías Díaz Padrón. Catálogo de la obra de Van Dyck en España Vol II, Instituto Moll 2012 pag 662-664, cat n 103, with image pag 663. Ottavia Balbi, Marquesa Balbi, as Van Dyck.

He notes that in Marqués del Carpio's inventory it appears referred a small picture representing a head of Women with hair dress adorned with pearls by Van Dyck.

6. Séguier1819, Catalogue valuations of Pictures the property of the Earl of Bristol at warehouse 19 April 1819 as by Rubens Unpublished (Hervey archives Bury St Edmunds).

Farrer 1913 Ickworth 1913.

Inventory 1952 of the most honorable 4th Marquess of Bristol deceased. Ickworth valuation for probate of Pictures drawings and miniatures. (as by Van Dyck).

Letter by Michael Jaffé to The Marquess of Bristol 1963, as by Van Dyck.

Ickworth, Suffolk. The National Trust 1994.

7. Since his young age Van Dyck was evidently obsessed by how to scrutinize the inner of the subject portrayed and thus had a natural tendency to concentrate his artistic efforts on the heads of the sitters or saints depicted. He may have been captivated by certain painters as Lucas van Leyden (Fig. B) or Jan Cossiers (Fig. 12) who were also focused in how to translate into canvas the feelings, the mood and the temperament of the subject representing it with great immediacy and compelling presence as if was a self-portrait.

In his youth in Antwerp, Van Dyck extensively trained his ability to depict the heads of Saints in preparatory oil studies (Fig. A), though we are not awared that he did studies for portraits in oil or in drawing. It is only in Genoa that he practiced the formula of creating an oil modeletto alla prima and ad vivum of the portrayed sitter, following his habit of not making preparatory drawings of the effigies. There, he sharpened his powers of observation and his ability to capture the physical and emotional physiognomy of the sitter. The reason for this new practice is that a newly arrived Van Dyck in Genoa was obliged to go to the palaces of his clients, mainly women, since it was not well seen, to come to pose in his studio. This social practice forced him to exercise that innate ability he had from a very young age to instantly grasp the personality of the sitter, reaching his peak of this practice in Genoa. However, we also see it in his second period in Antwerp, reflected in his oil preparatory sketches of Magistrates (Fig. C and Fig. D), much less impressive than the Genoese ones, and in the magnificent drawings and grisailles for the engraving series circa 1530 (Fig. E). In England, although he certainly had to go to palace on many occasions for royal commissions, for which he practiced preparatory drawing like that of Charles I (Fig. F), it is known that visits to Van Dyck's studio for posing by aristocrats were frequent. He developed a cordial relationship and entertained them with certain amusements to make the session more relaxed, which lasted no more than an hour. This allowed him to make preparatory sketches on the final canvas itself, all of which have disappeared except one that has come down to us representing the Royal princes Elisabeth and Anne (Fig. G).

Among the Genoese sketches, that of Marchesa Ottavia Balbi (Fig. 1), in an almost pristine state of conservation, shares its unique character with the one of Marchesa Grimaldi Cattaneo (Fig. 10), which, although of similar excellent quality, only comparable to the lost modeletto of Lucas van Uffel, it is somewhat retouched by a later hand. (Fig. 14, page 13, "Van Dyck, the Anatomy of Portraiture").

Another modeletto whose attribution has been questioned due to its poor state of preservation and a botched restoration is that of a woman's portrait in oil on canvas (Fig. H). Susan Barnes, in 2004, revised her opinion of not being autograph upon seeing a photograph from before the restoration of 1947 (Fig. I).

The preparatory oil study of Battina Balbi Durazzo, which was exhibited alongside that of Marchesa Balbi at the Genoa exhibition (Fig 25), although it has lost its shine, according to Susan Barnes, still retains reminiscences of Van Dyck's imprint.

It is generally assumed that the two nearly identical masterpieces by Van Dyck representing Lucas van Uffel were painted in 1623 in Venice (Fig. 9) (Metropolitan Museum, Herzog Anton Ulrich - Museum Braunschweig). Christopher White notes that, bearing in mind the closeness of the depiction between both heads, a rare preparatory oil sketch, now lost, should have been made by the Master to render both pictures. It is quite noticeable the parallelism in composition, attitude and general movement with Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo's modeletto (Fig. 10).

8. Gio Agostino had a single illegitimate daughter born in Antwerp, who by the terms of her father’s testament will gain her inheritance if she married one of the family. Susan Barnes opus cit catalogue of exhibition at the NGA "Van Dyck paintings" 1991 pag 146.

Susan Barnes in his catalogue raisonné 1997 suggest the thesis that the modeletto could be a preparatory study made alla prima of a painting whose replica was at the Denver Museum of Art.

Provenance of the Denver Museum van Dyck portrait of a Woman: Lord Meadowbrook, Julius Bohler Munich, Count Alessandro Contino-Bonocassi. Florence 1924. Reinhardt New York 1927, Senator and Mrs Simon Guggenheim 1931 by whom gift to the Denver Art Museum 1962, de-accessioned 27th January 2010 Christies New York lot 325.

9. Michael Jaffé date the modeletto circa 1521-1523 opus cit 1965, 2002 Susan Barnes, Piero Boccardo and Matías Díaz Padrón are keener to date the modeletto 1526/27.

10. Letter written by Michael Jaffé to the Marquess of Bristol informing that the modeletto is an autograph work by Van Dyck (1963).

Letter from the restorer to Susan Barnes, indicating the modeletto is in an excellent condition and that it shows an inscription on his upper left side with the name "Balbi" and a n12 in the low right side (1996).

11. Referred by Lucas Montoya. In "Crónica de los Mínimos de S F de P”, Madrid 1619. Grendi 97.

12. Bocardo, Magnani 1987. Catalogue of the exhibition "Van Dyck Genova 1997". Piero Boccardo "Ritratti di collezionisti e comitente" pag 29-58; Susan Barnes "Van Dyck a Genova" pag64-81. Eduardo Grendi 1997.

13 The Balbi family represented the new Genoese aristocracy, to some extent opposed to the old lineages of the Grimaldi, Espinola, Doria, Lomellini, or Cattaneo. A society characterized by its focus on women attested by the fact that the majority of Van Dyck's Genoese portraits are of women, and many of them do not have their corresponding pendant in men. The Genoese aristocracy formed a social circle that stimulates femininity as an attractive quality of women's image in an environment where fashion, jewellery, demeanour, sense of class, and economic power, are of vital importance. Add Stijn Alsteen, op. cit. 2016, Crendi 1997.

Boccardo, Magnani 1987; opus cit Boccardo 1997; Crendi 1997. Stijn Alsteen opus cit2016.

14. Boccardo and Magnani 1987; Susan Barnes Catalogue of the NGA exhibition 1991 pag 144-146 Catalogue of exhibition "Van Dyck Genova" 1997 pag 64-81.

15. Catalogue of exhibition "Van Dyck - Genova" 1997 pag 230-231, Dama Genovesa della Marchesa Balbi. Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo pag 248-249, Getildonna seduta Pag 282-283.

16. Michael Jaffé opus cit 1965, 2002; Boccardo and Magnani opus cit1987, Catalogue of the sale the East Wing Ickworth, Suffolk 11and 12 June 1996 lot 484 pag 173; Catalogue of the NGA exhibition Van Dyck paintings, November 1990-February 1991. Susan Barnes cat 24 pag 144 145. Susan Barnes Catalogue exhibition Van Dyck - Genova 1997 regarding the full-length portrait della Marchesa Balbi pag 230 - 31 and the modeletto 232- 233.

In this catalogue 1997 Boccardo finally accept the thesis of Susan Barnes as there is no documental evidence attesting his previous opinion regarding the identification of the sitter as the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi based on tradition and the Palace where the NGA portrait has been purchased.

17. Ickworth Suffolk the National Trust 1994; Sotheby's Catalogue of the sale "The East Xing Ickworth, Suffolk". 1996. Catalogue of the exhibition Van Dyck Genoa cat37 pag 232.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Susan J. Barnes, Piero Boccardo, Clario Di Fabio Laura Tagliaferro. Catalogue of the exhibition Van Dyck a Genova. Electa 1997.

- Susan J. Barnes, Nora de Poorter, Oliver Millar, Horst Hey. "Van Dyck a Complete Catalogue of paintings". Yale University Press 2004.

- Susan J. Barnes, Arthur K Wheelock Jr, Julius Held. Catalogue the exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Art. November1990 - February 1991.

- Susan J. Barnes" Van Dyck in Italy". PHD dissertation. New York University 1986 NC18.

- Bellori 1672. “Le vite dei pittori sculptors et architetti”. Rome 1672.

- Christopher Brown, Hans Vlieghe, Catalogue of the exhibition Koninklijk Museum Voor Schone Kunsten, Anvers 15 May-15 August 1999.

- Carlos Depauw & Carl Luitjen, Anton van Dyck y el arte del grabado. Fundación Carlos de Amberes, 2004.

- Matías Díaz Padrón, "Van Dyck en España" Prensa Ibérica 2013.

- Adam Eaken, Stijn Alsteens "Van Dyck the anatomy of Portraiture". Catalogue of the exhibition organized the Frick Collection, 2 March June 2016.

- Adam Eaker, “Van Dyck between Master and model”: The Art bulletin n97n2, June 2015.

- Eduardo Grendi. "Una familia Genovese fra Spagna e Impero". Biblioteca de cultura histórica 1997.

- Ickworth, Suffolk. The National Trust 1994.

- Michael Jaffé. "The Devonshire Collection of Northern European Drawings" Volume 1 Van Dyck - Runens. Umberto Allemandi &Co 2002.

- Michael Jaffé 1994. “On some portraits painted in Italy mainly Genoa”, in Barnes and Wheelock 1994, pag 135-50.

- Michael Jaffé 1997. “Rubens in Italy: A self-portrait”, Burlington Magazine n119, sept 1977.

-Erick Larsen "l'Opera completa di Van Dyck" Rizzoli editores Milano 1980.

- Alfredo Moir "Anthony van Dyck" Harry N. Abrams Inc publishes 1994.

- Leo van Puyvelde "Van Dyck" Bruxelles, Elsevier 1950.

- Xavier Salomon, "Van Dyck in Sicily 1624-25, painting and the plaque". Silvana 2012.

- Sotheby’s Catalogue of the exhibition the east Wing Ickworth Suffolk 11-12 June 1996.

- Alejandro Vergara. "El joven Van Dyck". Editorial Museo del Prado 2012.

- Christopher White "Anthony van Dyck and the Art of Portraiture" Modern Art Press.

NOTES

1. Letter from Michael Jaffé to the Marquess of Bristol stating that this modeletto representing a Genovese woman is an autograph work by Van Dyck dated 1963.

Michael Jaffé. "Van Dyck portraits in De Young Museum and elsewhere" in Art Quarterly vol 28, 1965 p44 n 31.

Michael Jaffé. "The Devonshire Collection of Northern European Drawings" Volume 1 Van Dyck - Rubens pag 71 Umberto Allemandi & co 2002. With image of the modeletto representing Ottavia Balbi, private collection and image of the drawing by Van Dyck representing a study of trials for portraiture, pen and wash Upsala, University library.

2. Susan Barnes" Van Dyck in Italy". PHD dissertation. New York University 1986 NC18.

Susan J Barnes, Nora Poorter, Oliver Millar, Host Vey. "Van Dyck. A complete Catalogue of the paintings". Yale University 2004, pag 233 cat n II. 112 reproduced as Van Dyck.

Susan J Barnes letter to my father indicating the modeletto is an autograph work by Van Dyck 1996.

3. The East Wing Ickworth Suffolk Sotheby’s sale 11 and 12 June 1996 484 acquired by my father. One year later I privately acquired the painting to my father.

4. Catalogue of the exhibition. "Van Dyck. Grande pittura e colezionismo. A Genova". Susan Barnes, Piero Boccardo, Clario Di Fabio, Laura Tagliaferro. Palazzo Ducale, Genova. Comune di Genova. Cat47 pag 232 image 233 Catalogue entry Susan J Barnes. Electa 1997.

Though I was informed by Sotheby’s the night before the sale that several very strong clients would be bidding at the phone, I only had the certitude that the Getty Museum had bided against my father, when in 2012, I met David Jaffé, in those days having left the Getty and working as an independent art historian, visiting a preview at Christies. During the conversation I show him an image of the modeletto, searching his Van Dyck expert opinion. He immediately answers me "you've got it", confirming that the Getty Museum failed to acquire this modeletto representing the Marchesa Balbi at Ickworth sale.

5. Matías Díaz Padrón. Catálogo de la obra de Van Dyck en España Vol II, Instituto Moll 2012 pag 662-664, cat n 103, with image pag 663. Ottavia Balbi, Marquesa Balbi, as Van Dyck.

He notes that in Marqués del Carpio's inventory it appears referred a small picture representing a head of Women with hair dress adorned with pearls by Van Dyck.

6. Séguier1819, Catalogue valuations of Pictures the property of the Earl of Bristol at warehouse 19 April 1819 as by Rubens Unpublished (Hervey archives Bury St Edmunds).

Farrer 1913 Ickworth 1913.

Inventory 1952 of the most honorable 4th Marquess of Bristol deceased. Ickworth valuation for probate of Pictures drawings and miniatures. (as by Van Dyck).

Letter by Michael Jaffé to The Marquess of Bristol 1963, as by Van Dyck.

Ickworth, Suffolk. The National Trust 1994.

7. Since his young age Van Dyck was evidently obsessed by how to scrutinize the inner of the subject portrayed and thus had a natural tendency to concentrate his artistic efforts on the heads of the sitters or saints depicted. He may have been captivated by certain painters as Lucas van Leyden (Fig. B) or Jan Cossiers (Fig. 12) who were also focused in how to translate into canvas the feelings, the mood and the temperament of the subject representing it with great immediacy and compelling presence as if was a self-portrait.

In his youth in Antwerp, Van Dyck extensively trained his ability to depict the heads of Saints in preparatory oil studies (Fig. A), though we are not awared that he did studies for portraits in oil or in drawing. It is only in Genoa that he practiced the formula of creating an oil modeletto alla prima and ad vivum of the portrayed sitter, following his habit of not making preparatory drawings of the effigies. There, he sharpened his powers of observation and his ability to capture the physical and emotional physiognomy of the sitter. The reason for this new practice is that a newly arrived Van Dyck in Genoa was obliged to go to the palaces of his clients, mainly women, since it was not well seen, to come to pose in his studio. This social practice forced him to exercise that innate ability he had from a very young age to instantly grasp the personality of the sitter, reaching his peak of this practice in Genoa. However, we also see it in his second period in Antwerp, reflected in his oil preparatory sketches of Magistrates (Fig. C and Fig. D), much less impressive than the Genoese ones, and in the magnificent drawings and grisailles for the engraving series circa 1530 (Fig. E). In England, although he certainly had to go to palace on many occasions for royal commissions, for which he practiced preparatory drawing like that of Charles I (Fig. F), it is known that visits to Van Dyck's studio for posing by aristocrats were frequent. He developed a cordial relationship and entertained them with certain amusements to make the session more relaxed, which lasted no more than an hour. This allowed him to make preparatory sketches on the final canvas itself, all of which have disappeared except one that has come down to us representing the Royal princes Elisabeth and Anne (Fig. G).

Among the Genoese sketches, that of Marchesa Ottavia Balbi (Fig. 1), in an almost pristine state of conservation, shares its unique character with the one of Marchesa Grimaldi Cattaneo (Fig. 10), which, although of similar excellent quality, only comparable to the lost modeletto of Lucas van Uffel, it is somewhat retouched by a later hand. (Fig. 14, page 13, "Van Dyck, the Anatomy of Portraiture").

Another modeletto whose attribution has been questioned due to its poor state of preservation and a botched restoration is that of a woman's portrait in oil on canvas (Fig. H). Susan Barnes, in 2004, revised her opinion of not being autograph upon seeing a photograph from before the restoration of 1947 (Fig. I).

The preparatory oil study of Battina Balbi Durazzo, which was exhibited alongside that of Marchesa Balbi at the Genoa exhibition (Fig 25), although it has lost its shine, according to Susan Barnes, still retains reminiscences of Van Dyck's imprint.

It is generally assumed that the two nearly identical masterpieces by Van Dyck representing Lucas van Uffel were painted in 1623 in Venice (Fig. 9) (Metropolitan Museum, Herzog Anton Ulrich - Museum Braunschweig). Christopher White notes that, bearing in mind the closeness of the depiction between both heads, a rare preparatory oil sketch, now lost, should have been made by the Master to render both pictures. It is quite noticeable the parallelism in composition, attitude and general movement with Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo's modeletto (Fig. 10).

8. Gio Agostino had a single illegitimate daughter born in Antwerp, who by the terms of her father’s testament will gain her inheritance if she married one of the family. Susan Barnes opus cit catalogue of exhibition at the NGA "Van Dyck paintings" 1991 pag 146.

Susan Barnes in his catalogue raisonné 1997 suggest the thesis that the modeletto could be a preparatory study made alla prima of a painting whose replica was at the Denver Museum of Art.

Provenance of the Denver Museum van Dyck portrait of a Woman: Lord Meadowbrook, Julius Bohler Munich, Count Alessandro Contino-Bonocassi. Florence 1924. Reinhardt New York 1927, Senator and Mrs Simon Guggenheim 1931 by whom gift to the Denver Art Museum 1962, de-accessioned 27th January 2010 Christies New York lot 325.

9. Michael Jaffé date the modeletto circa 1521-1523 opus cit 1965, 2002 Susan Barnes, Piero Boccardo and Matías Díaz Padrón are keener to date the modeletto 1526/27.

10. Letter written by Michael Jaffé to the Marquess of Bristol informing that the modeletto is an autograph work by Van Dyck (1963).

Letter from the restorer to Susan Barnes, indicating the modeletto is in an excellent condition and that it shows an inscription on his upper left side with the name "Balbi" and a n12 in the low right side (1996).

11. Referred by Lucas Montoya. In "Crónica de los Mínimos de S F de P”, Madrid 1619. Grendi 97.

12. Bocardo, Magnani 1987. Catalogue of the exhibition "Van Dyck Genova 1997". Piero Boccardo "Ritratti di collezionisti e comitente" pag 29-58; Susan Barnes "Van Dyck a Genova" pag64-81. Eduardo Grendi 1997.

13 The Balbi family represented the new Genoese aristocracy, to some extent opposed to the old lineages of the Grimaldi, Espinola, Doria, Lomellini, or Cattaneo. A society characterized by its focus on women attested by the fact that the majority of Van Dyck's Genoese portraits are of women, and many of them do not have their corresponding pendant in men. The Genoese aristocracy formed a social circle that stimulates femininity as an attractive quality of women's image in an environment where fashion, jewellery, demeanour, sense of class, and economic power, are of vital importance. Add Stijn Alsteen, op. cit. 2016, Crendi 1997.

Boccardo, Magnani 1987; opus cit Boccardo 1997; Crendi 1997. Stijn Alsteen opus cit2016.

14. Boccardo and Magnani 1987; Susan Barnes Catalogue of the NGA exhibition 1991 pag 144-146 Catalogue of exhibition "Van Dyck Genova" 1997 pag 64-81.

15. Catalogue of exhibition "Van Dyck - Genova" 1997 pag 230-231, Dama Genovesa della Marchesa Balbi. Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo pag 248-249, Getildonna seduta Pag 282-283.

16. Michael Jaffé opus cit 1965, 2002; Boccardo and Magnani opus cit1987, Catalogue of the sale the East Wing Ickworth, Suffolk 11and 12 June 1996 lot 484 pag 173; Catalogue of the NGA exhibition Van Dyck paintings, November 1990-February 1991. Susan Barnes cat 24 pag 144 145. Susan Barnes Catalogue exhibition Van Dyck - Genova 1997 regarding the full-length portrait della Marchesa Balbi pag 230 - 31 and the modeletto 232- 233.

In this catalogue 1997 Boccardo finally accept the thesis of Susan Barnes as there is no documental evidence attesting his previous opinion regarding the identification of the sitter as the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi based on tradition and the Palace where the NGA portrait has been purchased.

17. Ickworth Suffolk the National Trust 1994; Sotheby's Catalogue of the sale "The East Xing Ickworth, Suffolk". 1996. Catalogue of the exhibition Van Dyck Genoa cat37 pag 232.

Director of IOMR

April 2024

Download comparative study with images

It was on the occasion of the cataloguing of several works from the collection of the Marquess of Bristol at Ickworth House, when in 1963 Michael Jaffé, director of the Fitzwilliam Museum and professor of Western Art at Cambridge University, was captivated by the magnetism emanating from this ravishingly modeletto of a young Genoese woman traditionally considered as the Marchesa Balbi (Fig 1), assigning it, due to its vibrant execution and compelling gaze, to the talented hand of the prodigious painter, Anthony van Dyck, a work from his Genoese period. Years later, he identified the sitter as Ottavia Balbi, by relating it to the magnificent full-length portrait of the Marchesa Balbi, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Fig. 2), and to a sketch listed in the catalogue of drawings of the Devonshire Collection 2002 p. 71 (1).

In light of this discovery, Susan Barnes, the most respected authority on the study of Van Dyck in Genoa, confirmed its autograph nature, considering it as a paradigmatic example of the particular way the Master portrayed from life and alla prima the Genoese nobility in their palaces. Therefore in 2004 she included this modeletto as an autograph work in the catalogue raisonné of the artist (2).

In 1996, David Jaffé, curator of European paintings at the Getty Museum, confirmed its attribution to Van Dyck on the occasion of Sotheby's auction "The east Wing Ickworth House" 1996, in his failed attempt to acquire the work for the Getty Museum, after a crowded bidding war against my father (3). Shortly afterwards, we lent the work for the exhibition Van Dyck - Genoa curated in July 1997 by Piero Boccardo and Susan Barnes, exhibited at the Palazzo Ducale alongside one of its only pairs, the modeletto of the Marchesa Grimaldi Cattaneo (Fig. 3), and in harmony with the magnificent full-length portrait of the Marchesa Balbi (Fig. 2), which strongly recalls the portrait of Maria Serra Pallavicino by Rubens (Fig. 5) (4). Apart from Susan Barnes, who honoured us with her presence many times, among the many scholars and curators who saw the work in my House in Madrid, I would highlight Blaise Ducos, curator of Flemish painting at the Louvre, CD Dickerson head of European paintings and sculpture of the National Gallery of Art, Nicola Spinosa, director of the Capodimonte Museum, Micha Leeflang from the Catharijneconvent Museum and our friend, Matías Díaz Padrón, former director of the department of Flemish painting at the Prado Museum and a leading authority in Van Dyck, who, captivated by the charms of this portrait so well enhanced by the hand of Van Dyck, included it as a reference work in his Catalogue raisonné on Van Dyck's work in Spain (5).

We are therefore facing a magnificent example of Van Dyck's pictorial skills, representing one of the rising stars of Genoese society in the early 17th century, the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, and boasting an impeccable provenance that dates back uninterruptedly since more than two centuries, through the successive owners of the Bristol House, many of whose works, like this modeletto, were acquired during their periodic Grand Tours of Italy and sold centuries later in the Sotheby’s auction of 1996 (6).

As a tribute to this magnificent work, of my collection, I would like to delve into the three axes that make it a piece de résitance of great value in Van Dyck Corpus.

A) The paradigmatic character with which Van Dyck's portraiture genius is expressed in this modeletto.

B) The importance of representing such an iconic member of the Genoese family with stronger economic ties in Antwerp, as the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, who introduced Van Dyck to Genoa in 1621.

C) Its historical provenance from Ickworth House, owned by the Marquesses of Bristol. A family linked to Italy through their periodic Grand Tours.

A) The paradigmatic character with which Van Dyck's portraiture genius is expressed in this modeletto.

"… one could expect an oil sketch of this period to be of the highest quality.” Van Dyck Anatomy of Portraiture, 2016.

This modeletto, by its very nature, highest pictorial quality and pristine state of condition, contains, like none of the few that have survived, the quintessence of Van Dyck's portrait genius, his ability to spontaneously capture the very moment when the painter grasps the soul of the portrayed sitter and translates it onto paper with the freshness, looseness, and brevity of stroke that led him to reach the pinnacle of his Art in Genoa, as the greatest portraitist of the 17th century, a consideration already evident in his self-portrait at the age of just 16 (Fig. 7) and in his youthful masterpiece, the portrait of Cornelisz van der Geest (Fig. 6).

Oil sketches, made ad vivum, attest to a working method, which evolved from 1521 in Genova to 1528 in Antwerp towards the virtuosity of the drawing series and the grisailles for engravings achieved circa 1530/35 (Fig. E) and the rather prosaic oil sketches representing magistrates circa 1534 (Fig. C, Fig. D). This technique persisted in England through preparatory oil studies sketched directly on the original canvas, unfortunately now lost due to being covered by the final images elaborated by Van Dyck and his assistants in the workshop. However, none of these authentic icons of English portraiture, due to the ease, nonchalance, and melancholy of his sitters, retain the immediacy of his youthful effigies or the vivacity of gaze of the most probably lost modeletto representing the portrait of Lucas van Uffel, circa 1623 (Fig. 9), or the compelling presence of the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi’s portrait that we are studying here (Fig. 8) (7).

Only on some occasions does Van Dyck express himself with such confidence and brio as in this modeletto, in which a strong connection with the sitter can be perceived, a mutual magnetism that inspires the Master's intelligence and sensitivity in his process of capturing the psychology of the person in front of him. He does it intuitively, in a process similar to a self-portrait (Fig. 11, 12) that can only be achieved when one knows the model well, like Ottavia, whom he probably met as a child in Antwerp.

All of Van Dyck's representative portraits share a common characteristic empathy with the sitter that allows his genius to emerge, through a technique that anticipates Luca Giordano's fa presto and recalls Frans Hals (Fig. 16). Van Dyck fixes his gaze on this young woman, and in a few moments, his hand already resonates with the sprouts of imagination from which the soul of the Marchesa's effigy emanates allowing him to display the face on paper with just four strokes, seen in three quarters, and transfer that lively, interrogative gaze, in virtual contrapposto that pursues both him and us as we contemplate the work.

This sguardo, both dignified and acute, distant and communicative, typical of Van Dyck, which he perhaps draws from Rubens in his portrait of Brigida Spinola-Doria NGA (Fig 4), is intimately related to the way those magnetic eyes are painted, acting as a touchstone to discover the autograph character of his Genoese work. Van Dyck lightly marks the lower eyelids, a bit more the upper ones, skilfully and boldly delimiting both with a pinkish line and a hint of white; the irises, perhaps one more defined than the other, each show a spot of white, in almost identical and meridian position that fixes the sitter's gaze, giving the eyes that typical moist character of Van Dyck.

The ochre shadows that define the eyebrows, nose, chin, the corners of the lips, and a tremendously expressive mouth, with a slightly sensual gesture, in fine contrast with the striking pink of the cheeks and the stream of luminosity on the forehead, allow us to define the work as rather dramatic, where the interplay of light and shadow, il chiaroscuro, highlights the significantly individualized features of the Marchesa's countenance. An imprint concentrated on her powerful gaze and the subtly provocative expression of her lips, contributing to give a halo of femininity to the work (Fig. 13).

The chestnut imprimatura that stands out from the brown background treated in a very loosely manner, as befits a modeletto, where the somewhat casual hairstyle of the model reveals a bun very characteristic of Genoese fashion, adorned with small pearls, authentic flashes of light, painted with the masterful liveliness and lightness that characterizes the Master, from which hangs a round adornment only sketched, but which could well identify the Marchesa, all this leads us to maintain Susan Barnes' thesis, that places this modeletto in the last Genoese years, at least four years after the National Gallery of Art portrait of the Marchesa Balbi made by Van Dyck surely on the occasion of her marriage to Bartolomeo Balbi, as arranged before his death in 1621 by Gio Agostino Balbi, Ottavia's father. On the contrary, this modeletto could well be related, as Susan Barnes does in her catalogue raisonné, to another later portrait of the Marchesa, of which the portrait in the Denver Museum of Art could be a replica, sold in poor state of condition and which, after being recently acquired by a private collection and carefully restored, has shown to have sufficient quality to be considered a Van Dyck (Fig. 14) (8).

This dazzling modeletto, already excellent for its brevity, immediacy, and ingenuity, would not impact us in the way it does, if it were not for the fact that Van Dyck, in a display of technical virtuosity in its looseness very characteristic of him and other contemporary geniuses such as Velázquez (Fig. 15) and Frans Hals (Fig. 16), dresses the model with a ruff that, due to the lightly, lively, and vivacious way its brocades are rendered, gives the whole an ethereal, almost spectral nature. Something that we also find in the modeletto of the Marchesa Grimaldi Cattaneo (Fig. 10), being a hallmark of these Genoese sketches and especially of some of his last Genoese paintings.

This modeletto (Fig. 13), with its slight tenebrism, only Caravaggesque in how it illuminates the face, although not in its pictorial and lively technique, far removed from the luminous clarity of the portraits of Antwerp, like that of Gaspard Charles van Nieuwenhoven (Fig. 17) of the Phoebus Foundation, but with the same esprit and brio in the brushstroke, can be securely dated to the end of his stay in Genoa around 1627 and would correspond to a portrait of Ottavia when she was about 18 years old, from which the portrait formerly in Denver Museum of Art would also derive, coinciding with the year she becomes Marchesa Balbi upon the death of Gerolamo Balbi, her husband's father, merging the two family lines in her (9).

From this late Genoese period, we can cite as examples, the remarkable portrait of De Wael brothers (Fig. 18) where Van Dyck culminates a delicate chiaroscuro in the treatment of the features to sharpen the rendering of each brother's distinct temperament, the portrait of Porzia Imperiale and her daughter (Fig. 19) Francesca Maria, who displays a similar gaze, both in its angle of vision and intensity, the portrait of the Lomellini family (Fig. 20), where one can perceive in a stellar manner the warlike atmosphere in which Genoa was immersed as a result of the War with Piedmont, which we also observe in the equestrian portraits of Gio Paolo Balbi and Anton Giulio Brignole-Sale, in which Van Dyck combines his typical sprezzatura with an economy of means and efforts that characterizes this period and allows his prodigious artistic genius.

B) The importance of representing a member of the Genoese family with stronger ties in Antwerp, such as the Marchesa Ottavia Balbi, who introduced Van Dyck to Genoa.

This modeletto has traditionally been considered by the Bristol House as a portrait of the Marchesa Balbi (Fig. 23). In its upper left side, there is an ancient inscription with the word Balbi, by virtue of which it could be presumed that it was acquired from the Balbi family; whether that inscription was made in Italy or later in England is unknown. Its relation to Ottavia Balbi is first pointed out by Michael Jaffé in 1963 (10).

The Balbi family was very well established in Antwerp at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century, where they opened branches of their textile and banking businesses, to the point that at least three of its members were Consuls of Genoa in Antwerp: Bartolomeo Balbi during the years 1573 and 1592, marrying Lucrezia Santvoort in 1572, Gerolamo Balbi in 1585 and 1592, and Gio Agostino 1610, 11, and 1615 also marrying a citizen of Antwerp, Ines. All of them raised their children in Antwerp, with Gio Agostino being the one who staid longer there, founding the convent of the minorities of Saint Francis of Paul in 1615. He had an illegitimate Flemish child, Ottavia, who by the terms of his testament was obliged to marry a member of the family in order to gained his inheritance. Gio Agostino certainly met young Van Dyck who already in the 1620s had an independent workshop, as attested by the portrait, now disappeared, that Van Dyck made of him, just before his death in 1621 and his departure to Italy (11). It is therefore generally assumed that the Balbi family introduced him to the aristocratic Genoese environment, and it is very likely that he stayed at their Palace in Genoa when he was not lodging at the house of the brothers Lucas and Cornelis Wael. Proof of the importance of this family to Van Dyck is that today there is documentary evidence of nine portraits by Van Dyck related to the Balbi family, and it is believed that he must have painted many others that are not registered as such in the inventories of their palaces (Fig. 1, 2, 14, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 31) (12).

In this sense, adverse historical circumstances for the family, such as the participation of the Marquis, Bartolomeo Balbi (Fig. 26), and his brother Gio Paolo (Fig. 27) in the conspiracy against the Republic in 1649 and their subsequent arrest, led to the inventories of the works of art belonging to the main branch of the Balbi family being probably falsified to avoid being seized, with Bartolomeo himself making an inventory just before his arrest where he includes the properties left in inheritance by his father, Gerolamo, who died in 1527. This would explain the existence of numerous portraits by Van Dyck of members of this branch of the family whose identification of the depicted sitter is not well documented and depends today only on tradition or the palace from which they come, as is the case with the portrait of the Marchesa Balbi of the NGA (Fig. 29) and the modeletto of Ottavia Balbi that we are studying (Fig. 28). In other cases, the portrait, well documented, would have been apparently lost, probably because it was hidden to protect it from the police of the republic, such as the well-known equestrian portrait of the Marquis, Bartolomeo Balbi (Fig. 26), or, in order to avoid its identification by the Genoese authorities, the likeness of the portrayed person was even changed for another member of the family not pursued, as occurred with the equestrian portrait of Gio Paolo (Fig. 27), to which they modified the face to that of Francesco Maria Balbi. This circumstance greatly hinders the documentary tracing of the portraits of the principal line of the Balbi family and makes it necessary to delve deeper into other aspects, such as family tradition, provenance, physiognomy, dress style, or the jewels worn by the personages, to identify the individuals depicted (13).

The case of Marchesa Ottavia Balbi is paradigmatic of this issue insofar as, although there is no documentary evidence to attest to it, we have the certainty, as it makes no sense to presume otherwise, that when Van Dyck arrived in Genoa, he must have portrayed Ottavia, the illegitimate Flemish native daughter of the recently deceased Gio Agostino, his friend and promoter of his trip to Italy, especially considering that, following her father's instructions, she married Bartolomeo, the heir of the Balbi Marquisate belonging to the other family line. Consequently, Ottavia Balbi became the true star of Genoese society at the time, as the result of an accumulation of family wealth and power in this young woman who would become Marchesa Balbi in 1627 upon the death of Gerolamo Balbi, her husband's father (Fig. 28, 29, 31, 33).

Of all the portraits related to the Balbi family, three correspond to the same lady whose countenance is similar to the portrait considered of the Marchesa Balbi at the NGA:

- One of the authentic icons of Genoese painting, the portrait of the Marchesa Balbi painted by Van Dyck in 1623 currently at the National Gallery of Art (Fig. 29), represents Ottavia when she was about 14 years old, as reflected in her rounded and somewhat childlike features, which Van Dyck dignifies with a majestic and rather disproportionate green velvet dress studded with gold brocades, showing her with an artificial and forced air of superiority emphasised by the low point of view of the composition and the way she looks from her height; as if this teenager born in Antwerp, whom he knew as a child, was still not accustomed to this pomp required by her recent rank and that her blood did not run with that haughty nature so characteristic of Genoese society. Something that Van Dyck, did not want to silence, by placing those hands in an artificial manner, with a determined intention to express a certain discomfort. All this in total opposition to the elegance and natural bearing of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo who, in her portrait, also currently at the NGA (Fig. 30), advances nonchalantly in space with the parsimony of a swan, showing with naturalness her origin and aristocratic education. The portrait of the Marchesa Balbi currently at the NGA comes directly from Giacomo Balbi, descendant of the principal line of the Balbi, to which Bartolomeo Balbi, Ottavia's husband, belongs (14).

- The recognition of Ottavia Balbi's physiognomy with the Marchesa Balbi depicted in the NGA portrait allows the same title and name to be given to a lady portrayed by Van Dyck who has the similar facial features (Fig. 31) and, coincidentally, is seated with her hands and body in the same position as in the NGA portrait. She also wears a round ornament near her ear that we also see in other portraits of Ottavia Balbi. The portrait belongs to the current owner by inheritance of the same line of the Balbi as the NGA's portrait, coming from Giacomo Balbi, great-grandson of Francesco Maria Balbi 1619-1704 (15).