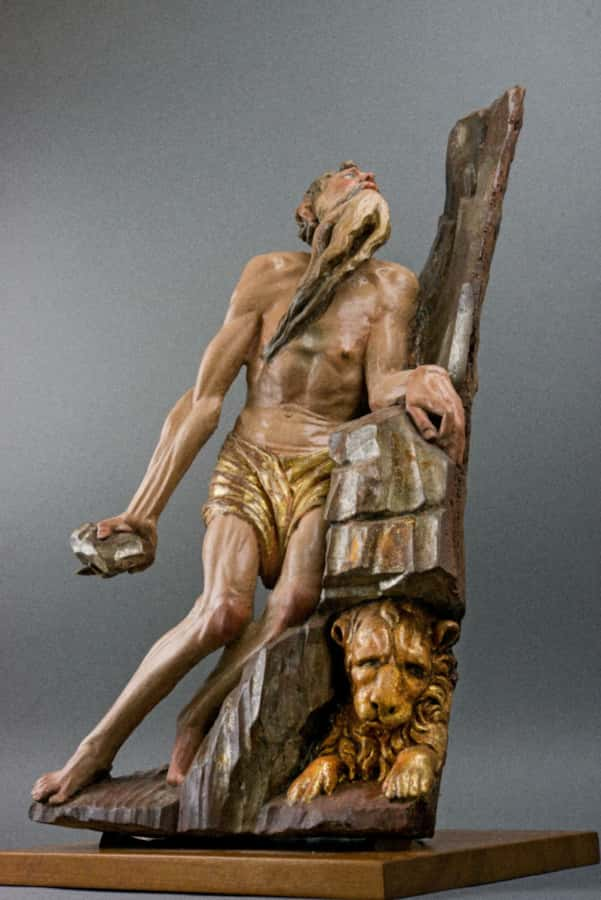

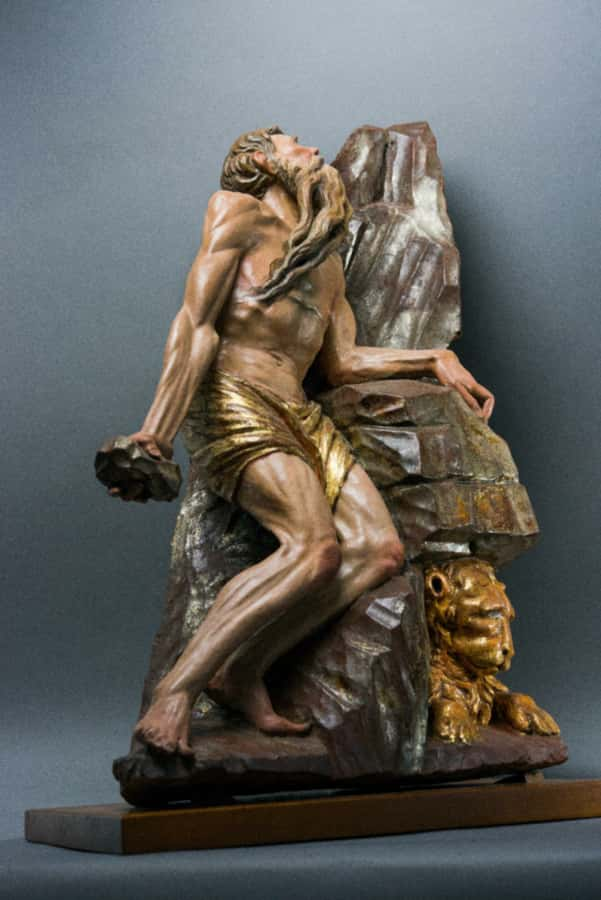

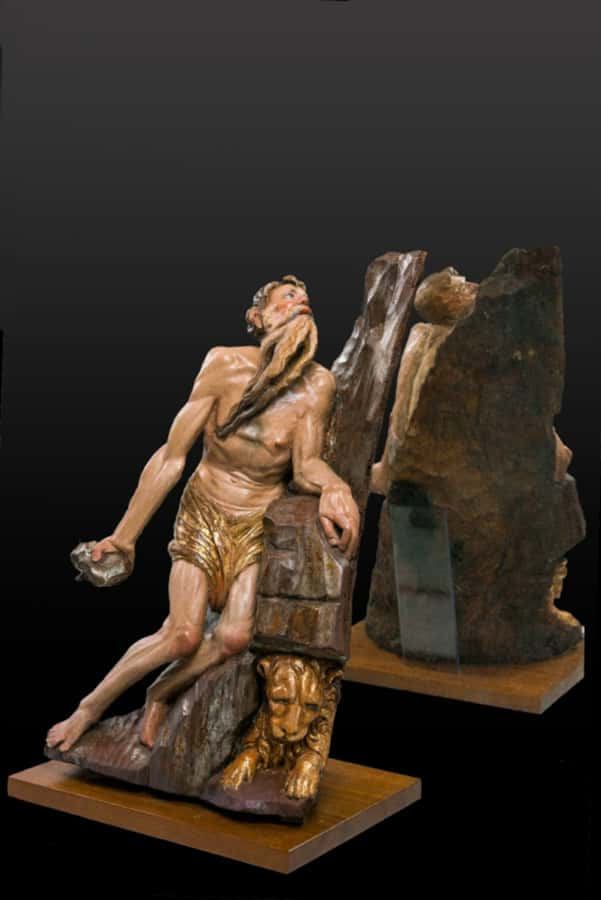

Saint Jerome

Juan de Valmaseda

Dated circa 1530

XVI century Castillian school

Material: polychrome walnut wood

Exhibited at the Cathedral of Toledo December 2017 / February 2018

Essays

1. read essay by JMParrado del Olmo

2. study by Carlos Herrero Starkie

3. Book “Treasures of Spanish Renaissance Sculpture, The origin of the Spanish Manner“

Description

There are occasions when a work of art surpasses the artistic recognition won historically by the author inasmuch as its intrinsic greatness goes beyond everything we know about him and serves to show us the way to rediscover him and study all his Corpus with modern eyes which may appreciate new aspects of his work.

We find ourselves facing a Masterpiece of the Spanish Renaissance to which all the excellences of that period converge when the Spanish artistic genius blossoms forth. That is why it acquires a paradigmatic significance within the IOMR collection. We find fully expressed in this magnificent representation of Saint Jerome the eternal values of expressivity, immediacy and modernity of Spanish Art to the same extent as they are expressed by El Greco, generations later, in his work in Toledo.

Its author is Juan de Valmaseda, not Alonso Berruguete or Diego de Siloé, as many would have wrongly thought at first sight, but an artist relatively unknown to international scholars, which makes this discovery all the more exciting, because it means the rise of an artist of an outstanding importance in the Spanish Renaissance, though fallen into disregard, with many works which must be studied with all the attention they deserve.

The first deep studies on Valmaseda’s work are carried out by a German, Georg Weiss, a great lover of Spanish Art, who assigns to him many important sculptures of the Capilla del Condestable at Burgos Cathedral. J. Camón Aznar and J.M. Azcárate both support this very positive opinion of the artist. M. Gómez Moreno concentrates his studies on Alonso Berruguete and Diego de Siloé in his book “Las Águilas del Renacimiento Español” where he consacrates these artists as the interpreters of classical gestures and, to a certain extent, applies discredit to Juan de Valmaseda , considering that his tardo-gothic artistic shapes did not develop into the genius which was foreseen in his early works. Valmaseda’s scarcely documented work has remained virtually trapped by history between those great names. The artistic greatness of the work we are now studying in a way contradicts this historiographic approach and indicates to us that Spanish Renaissance sculpture has to be revised in the light of the modern manner of Juan de Valmaseda .

Juan de Valmaseda, Vasco de Zarza, though so tremendously Italian, and Felipe Bigarni of French origin, constitute the artistic environment which Berruguete encounters on his return from Italy in 1518. Valmaseda, however, is the only genuinely Castilian artist endowed with an artistic talent which could receive the influence of the “Eagles of Spanish Renaissance” autonomously, without surrendering to them. In fact, Valmaseda is already a formed artist of about 30 years of age, and had participated in monumental works such as the altar-piece at Oviedo and in 1519 signed the contract of the Calvary for the high Altarpiece of Palencia Cathedral; this is a work which, for its monumental size and greatness, may be considered one of the supreme Castilian artistic works of its time in which Valmaseda demonstrates a great sensitivity and a lack of idealization of forms as a sculptor deeply rooted in a late gothic style which clearly defines the religious passion of Castilian people.

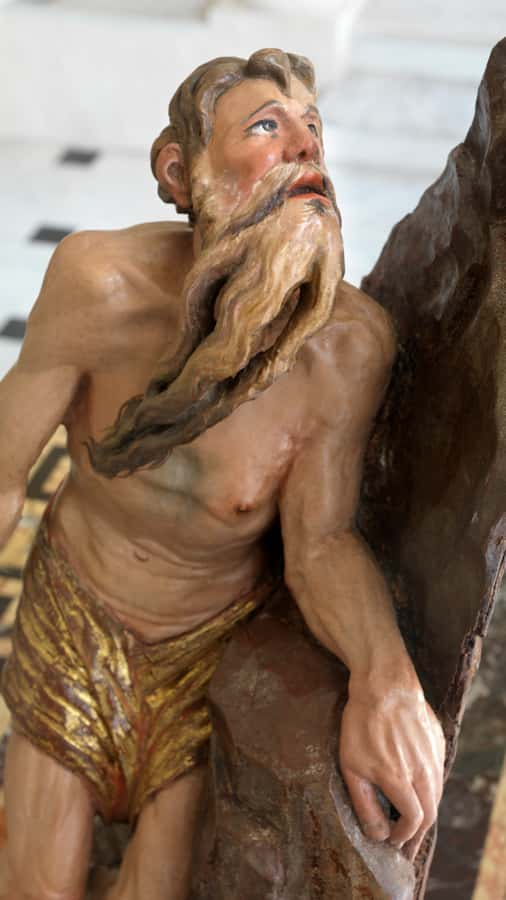

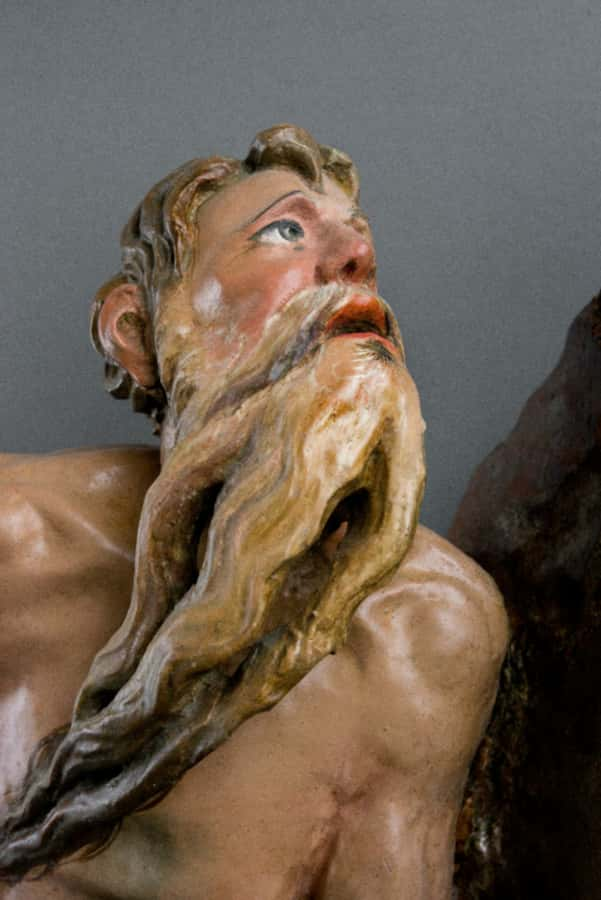

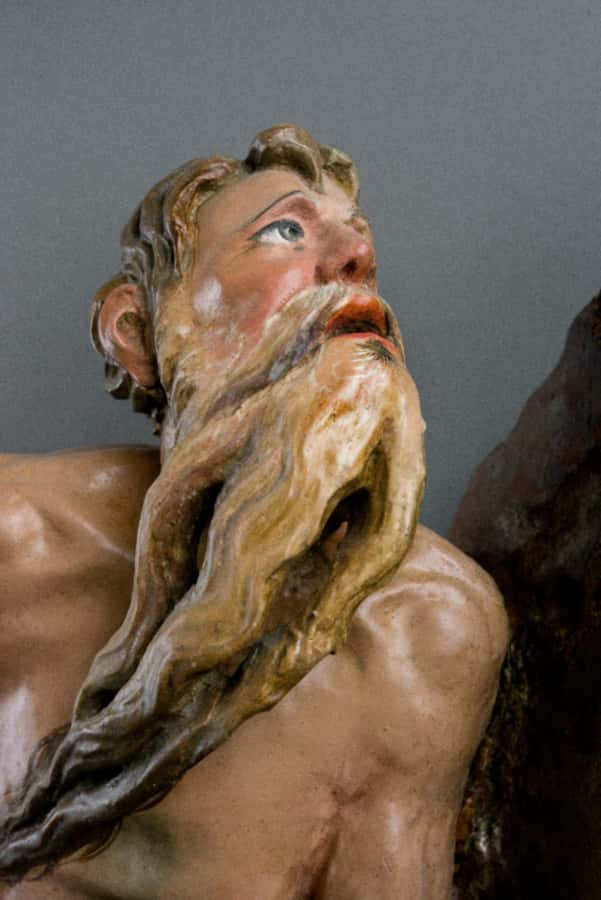

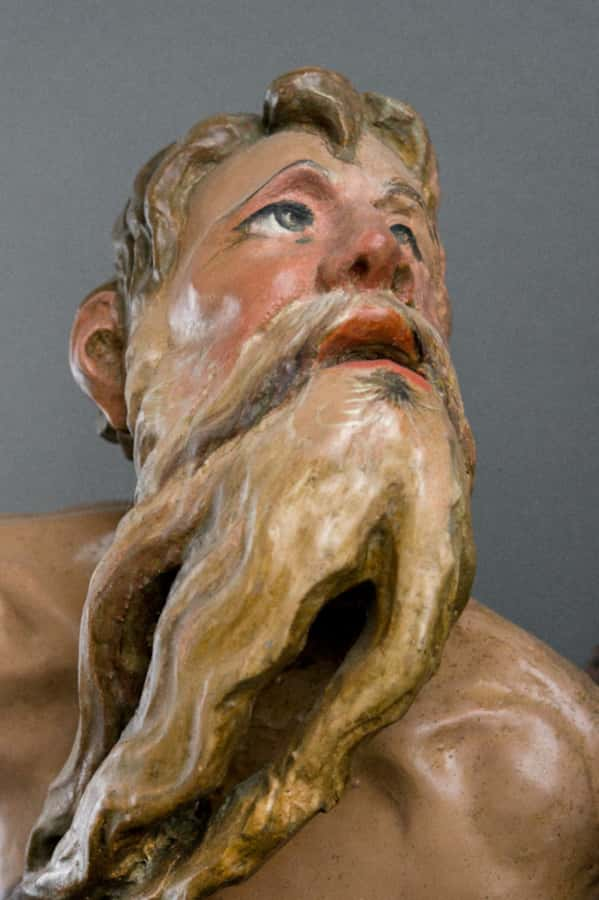

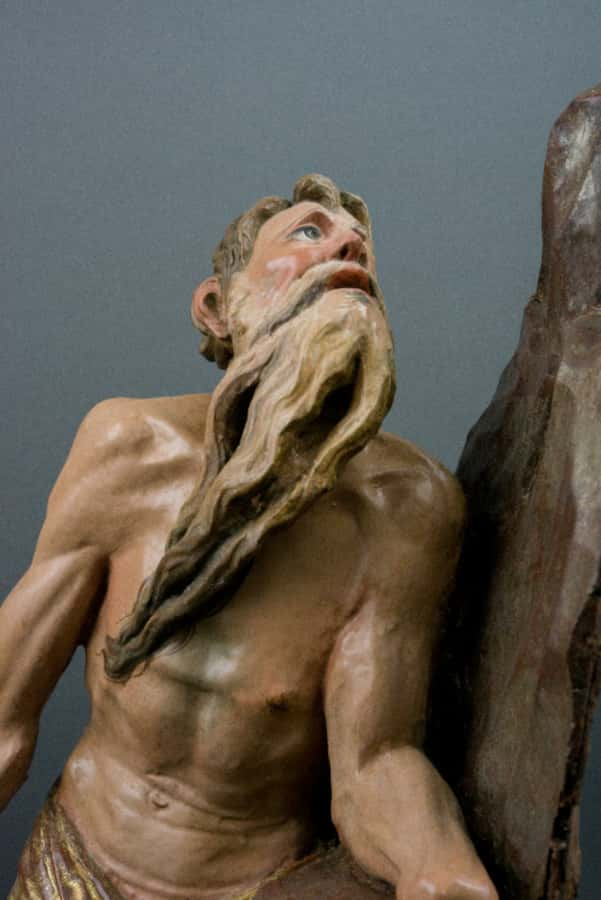

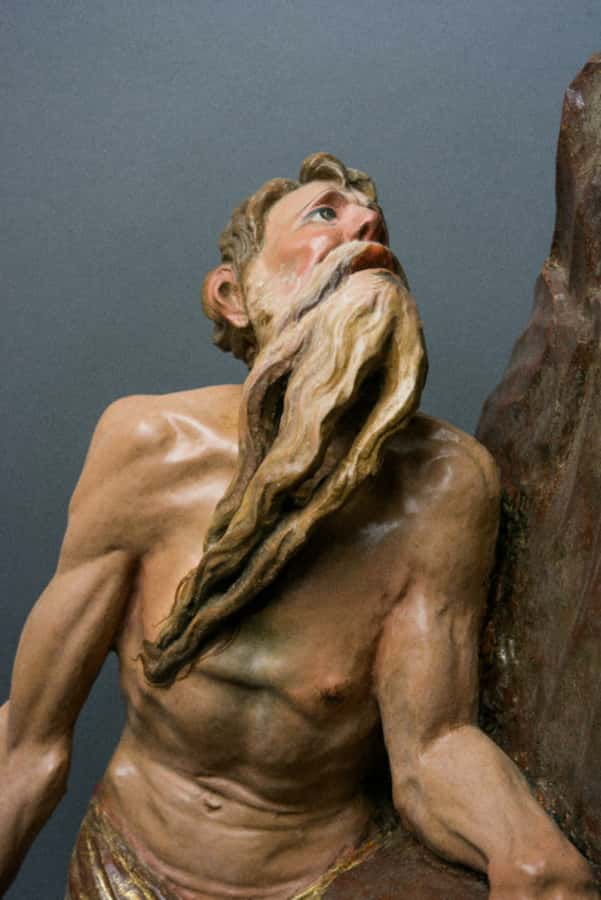

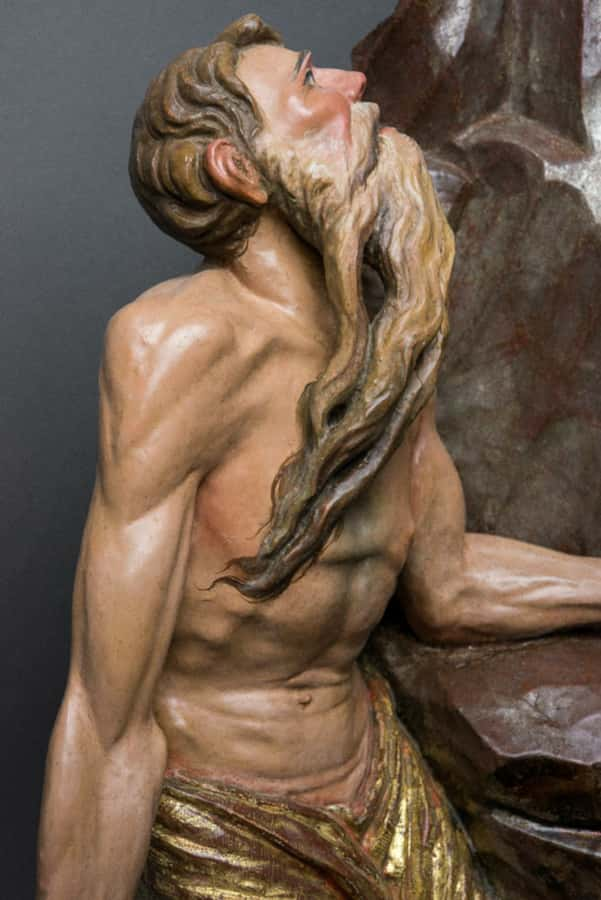

We, however, already observe specially in the Calvary of Palencia Cathedral, the touches of inspiration which make Juan de Valmaseda stand out as a genius with an immediate and evident artistic style completely of his own. He creates a canon of Calvary in which he combines in a masterly way the absolute rigidity of Christ with the sensational movement of Our Lady in a delicate contraposto to the Saint John from whose half-open mouth drips an overwhelming sorrow which reminds us of the newly discovered Laocoonte. We shall see something of all this later in Alonso Berruguete in his altar-piece of Mejorada de Olmedo and in the one of San Benito in Valladolid. This artistic formula which was so striking must have been very successful in view of the number of Calvaries attributed to him. We also find other touchstones which reveal his sculptor’s hand such as a straight nose, lean faces, prominent cheek bones, pointed beards and hair which falls in tangled locks, feet with outstretched toes and hands calmly crossed. All this treated in a succinct, expressionist manner, as it is executed in our St Jerome.

In 1520 Valmaseda is active in Burgos where he most probably worked in the Capilla del Condestable at the Cathedral. G .Weise, J. Camón Aznar, JM.Azcárrate and even M. .Gómez Moreno for a while, have attributed the magnificent group of a deceased Christ sustained by angels in the altar-piece of Santa Ana, the San Cristóbal and the San Sebastián in the altar-piece of San Pedro, and the figures of Our Lady and Saint John, swaying together in a movement so characteristic of him , in the high altarpiece of this chapel. All these attributions were later rejected by Gómez Moreno and by Francisco Portela, ascribing them to Diego de Siloé. No doubt the attributive points questioned regarding these two masters were confused until Manuel Gómez Moreno, patriarch of Spanish Renaissance scholarship, solved the polemic by deciding in favour of his choice Spanish Renaissance sculptor, Diego de Siloé.

In 1524 Valmaseda carries out the Calvary for the chapel of Christ in León Cathedral, accompanied by four Apostles; the best one is Saint John, with eyes lost in reverie and a face of a rather feminine and childlike beauty which we shall constantly encounter in Valmaseda’s later work. In this group Saint John is leaning against a tree whose gnarled knots and branches remind one of Siloé. His San Lucas wears spectacles just like those worn by Saint Jerome in the “Pietà de Desplá” by Bartolomé Bermejo. From 1524 onwards we see clearly the influence between Berruguetesque and Siloésque styles. The splendid altar-piece of Santa Columba of Villamediana (Palencia) belongs to this decade; its quality, however, is rather unequal, though in the relief work of the “Lamentación” and in the fabulous “San Jerónimo sedente” Valmaseda rises to celestial heights in the expression of pathos. The Our Lady and the St John, now in the Lázaro Galdiano Museum, also belong to this period. The “Lamentación” of the church of Santiago de la Puebla (Salamanca), attributed to Bigarni by most scholars, but which, after a comparative study regarding other “Lamentaciones”, should also follow the stream which links Siloé and Valmaseda and thus distances him from Bigarni. .

The 1530 decade, to which our St Jerome corresponds, marks the highest development of Valmaseda’s style; when his work reaches a synthesis between his underlying Gothic background, loaded with its strong expressivity, and the Italian influences filtered by Alonso Berruguete’s and Diego de Siloé’s interpretations. The Masterpiece of this period is without any doubt the altar-piece in the chapel of San Ildefonso of Palencia Cathedral, of markedly strong Siloesque characteristics in its smooth composition where Valmaseda combines in a masterly way medallions with figures in contraposto so that the scene seems to acquire an almost musical rhythm. We must draw attention to the magnificent relief work of Saint Jerome with its meticulous pictorial technique, whose lion is very similar to the one of our sculpture and the beautiful relief representing a nativity with the Wise Kings. The medallion, however, which crowns the altar-piece, representing the “Pietà”, recalls to us the other “Pietà” which Alonso Berruguete in 1529/1530 did for the chapel of the Colegio de Santiago de Fonseca in a strong Michelangelesque spirit, specially in the way Christ lets Himself fall into Our Lady’s lap; though, in Valmaseda’s case, taking the form of an arabesque with a certain Gothic mannerism.

We find ourselves facing a sculptor not well known in modern times who, however, has been able better than anyone else, to create compositions which became easily recognisable archetypes in his time, and which had great success in Castile during the first half of the XVIth century. Valmaseda creates various compositions which become canons during the Spanish Renaissance as are his Calvaries, his active Virgin Maries who appear to dance with swaying motion, with the Saints; his allegorical representations of death which influence so much Spanish XVII century sculptors; his childlike youths with rather feminine features, which our sculptor likes to repeat in his Saint Johns and his many San Sebastians which we see in Palencia Cathedral, in Santa Columba or in the Rodriguez Acosta collection ; I would even include in this group the magnificent San Sebastián, at present in the London market, attributed to Berruguete and which I would be inclined to assign to the best work of Valmaseda, due to his childlike face, elongated figure , sculptural technique, which is harsh in the moulding of the muscles and specially in the ribs of the youth (far from the softness rendered by Berruguete’s direct disciples) and due to its movement similar to other San Sebastians made by Valmaseda in which the evident lack of balance of the figure does not finish in the Berruguetesque spiral rotation, to which our Master adds with an artificial position of arms which make no concession to what is natural.

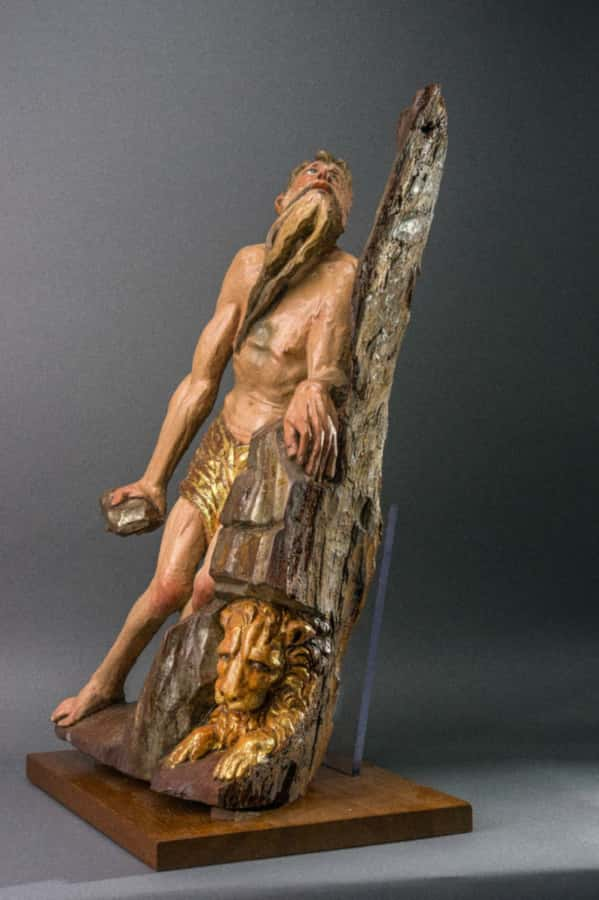

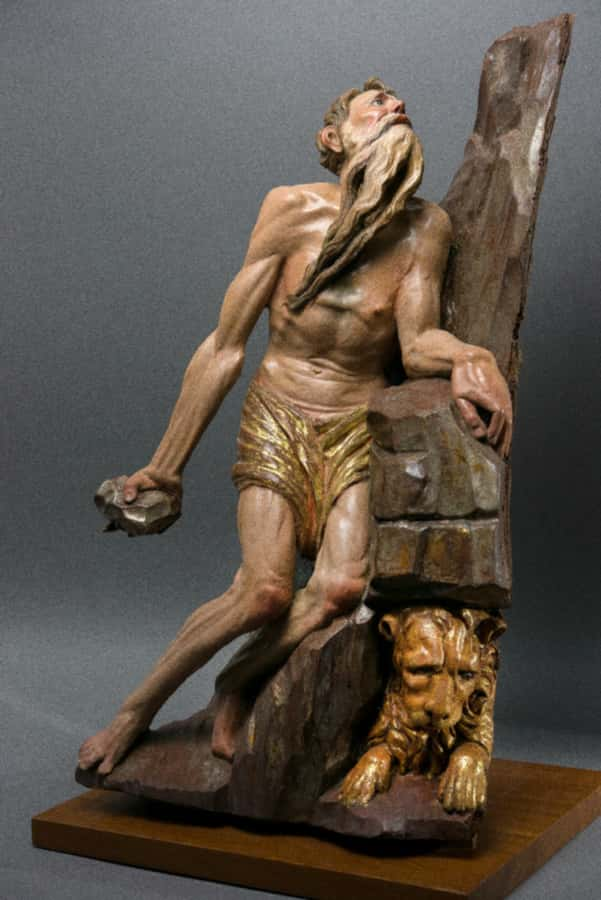

The work we are now studying represents a Saint Jerome in a state of ecstasy due to a supernatural vision of Christ; the scene is set in rocky surroundings, he holds in his hand a stone and is accompanied by a Lion. In this scene we observe strong Berruguetesque influences, above all, as Parrado indicates, in the composition “en serpentinata” and the unbalanced position of the Saint. It presents analogies in design between this sculpture and the St Jerome by Siloé in the chapel of the Condestable of Burgos Cathedral, specially due to the Saint’s firmly out stretched arm, the crouching position of his legs and the lion. All this makes us confirm for stylistic reasons the date of execution, in the decade of the 1530s, maintained by Parrado, which is when Valmaseda’s art reaches its highest quality, thus fulfilling excellently the fusion between his tardo-Gothic roots and the Italian influences of Alonso Berruguete and Diego de Siloé which, irritating ever more his strong expressionism, were now enrolled in a canon of beauty.

On finding ourselves, however, facing a masterpiece, the greatness of our St. Jerome lies in its originality. For this reason it would be wise to compare this sculpture with the other Masterpieces of Saint Jerome of the Spanish Renaissance, which in themselves would make a wonderful exhibition:

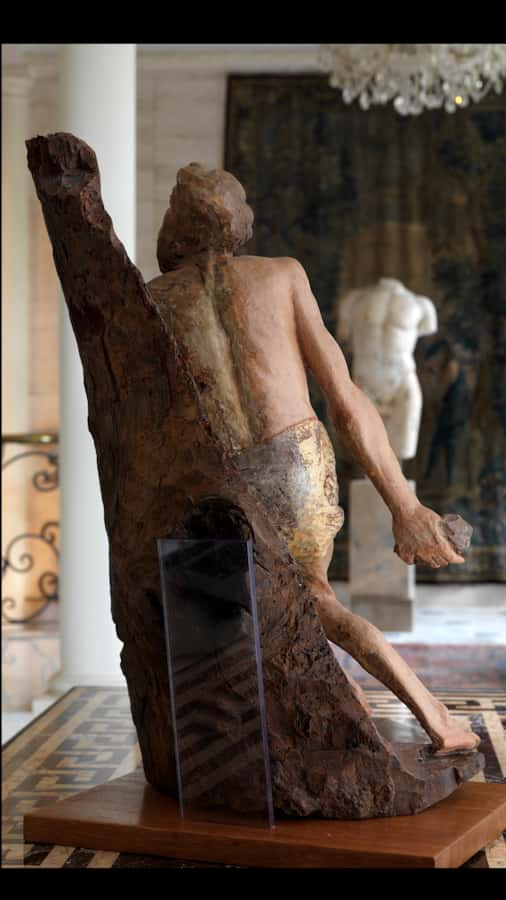

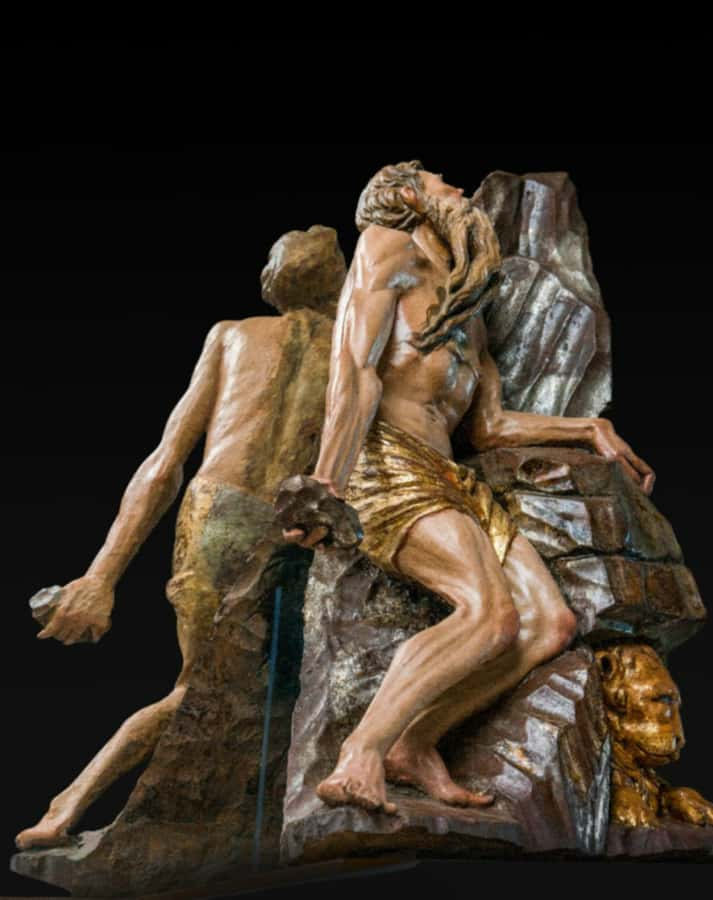

In opposition to the meticulous technique of Siloé in his St Jerome , Valmaseda simplifies the sculptural moulding of the muscles, rendering sketchily bones and tendons; he scarcely carves the outlines of feet even to the point that, if we observe the sculpture at the back, we shall see legs in oblique position, which is typical of Valmaseda, but formed in a succinct way that surprises us by its tremendous modernity, and by not making the slightest error in design. It is all perfect in its simplicity.

Facing the Laocontesque character of the Saint Jerome by Berruguete, we are overwhelmed by the expression of a both human and animal sensation of tremendous suffering regarding the chaos of the universe without the slightest trace of any religious sense; Valmaseda, on the contrary, is completely devoted to rendering the link between the Saint and the supernatural, expressing a profound faith.

On the other hand, Valmaseda surpasses the St. Jerome of Torrigiano, who is excellent in his artistic technique and in the originality of his design due to his movement forward, but lacks, in my opinion, any religious expression. In the passionate expressivity of his St. Jerome and in the impressionistic nature of his technique, lies the magnificently natural and the real presence in space that Valmaseda gives to the St Jerome which we are now studying.

Finally, if we compare it with the St Jerome of the Church of San Francisco at Medina de Rioseco, by Juan de Juní, there we would find ourselves facing a work of comparable expressivity, imbued by an early baroque style. Valmaseda offers us a composition captivated by the sense of movement worthy of Michelangelo’s slaves or Miron in his “discopolo”, based on a simple sloping diagonal. On such an evident simplicity lies the beauty of the sculpture.

Our St. Jerome calls on fervent Castilian believers to understand the irrational strength of the passion which the Saint feels. It is a question of faith and of Divine Grace which Valmaseda expresses and he does so with an absolutely masterly scarcity of resources, just by maintaining the Saint’s balance thanks to his outstretched arm and to the extremely upright position of his face which directs his look at the rock. A diagonal composition adjusts according to the physical inclination of the sculpture itself and therefore of the Saint who, due to this circumstance, seems to be alive and to maintain his balance thanks to Divine Grace itself.

At the beginning of the XVIth century we only find other examples representing the same sentiment of faith in Titian’s Saints, specially in the St Jerome, a small panel at the Escorial and, above all, in the magnificent Saint Jerome by El Greco, today in the National Gallery of Art in Washington; the three of them following a similar composition. In fact, all El Greco’s work emits, due to his spirit and his expressionist painting, an evident parallelism to Valmaseda. We also find it in the obsession with movement of the baroque, specially in Bernini. For this reason we can affirm that Valmaseda, like Berruguete, anticipates the new artistic currents which triumphed various generations later.

The rock which provides a setting for the Saint with polychromed silver “corlada” decoration at the front and with all nature’s rough strength on its reverse, enriched with a beautiful knot, fulfils a fundamental function in the work, since, on the one hand, it prolongs the Saint’s look to a supernatural scenery which we only intuitively imagine, and, on the other, it surrounds the sculpture so that it allows the spectator to have a different vision depending on the angle from which he looks.

Here lies another of the great achievements of the sculpture. By means of a mechanical rotation system, applied at the base of the sculpture, the spectator discovers unknown angles of the work which are incredibly beautiful: the sculpture seen side ways where the Saint appears virtually leaning on the rock, with only his hand and his mystical expression perceived; the vision of the Saint’s back, perfect in its unfinished state and of a Greek elegance which ends in sketchily rendered legs folded in an almost symphonic movement. Lastly, when we contemplate the reverse side of the sculpture, the piece shows there all its modernity as the walnut wood trunk, shaped like a flint stone, gains as the protagonist, and St. Jerome’s face scarcely stands out revealing his unfinished part. Can there be any more modernity in this scene? How much it reminds us of Michelangelo and his slaves, how much we are moved emotionally by this struggle between the spirit and the material, between polished and unfinished, areas in this conflict produced by forms in their intent to free themselves, in this case, from a wooden trunk!

Without any doubt, as indicated by J.M. Parrado del Olmo, we shall not be exceeding ourselves if we consider our Saint Jerome as one of Juan de Valmaseda’s works where his Art shines out in all its splendour and, armed with this credit, it should strive for the place which corresponds to him in the sculpture of the Spanish Renaissance with the same rights as the already consecrated great figures of Alonso Berruguete, Diego de Siloé and Juan de Juní, whose representations of Saint Jerome cast no shadow on this sculpture but indeed enhance it with a greater and more expressive passion, which is all the more profoundly Spanish and therefore a more essentially modern.

Carlos Herrero Starkie

Bibliography

- Azcarrate, J Mª: La escultura del siglo XVI español, Volumen XIII ARS Hispanal,1958.

- Camón Aznar, José: La escultura y la rejería del Renacimiento español. Espasa Calpe, 1975

- Gómez Moreno, Manuel: La escultura del Renacimiento español, Firenze-Barcelona, 1931.

- Gómez Moreno, Manuel: Las Águilas del Renacimiento Español, Madrid, 1941.

- Parrado del Olmo, JMª: Los escultores seguidores de Berruguete en Palencia. 1981.

- PORTELA SANDOVAL, Francisco José: La escultura del Renacimiento en Palencia. Palencia, 1977.

- SANCHEZ CANTON, F.J.: Dibujos españoles. (II) Siglo XVI y primer tercio del XVII. (III) Madrid, 1930.

- WEISE, Georg: Spanische plastik aus sieben Jahrhunderten. Reutlingen, 1925-1932,III,II.

Images

Fig. 1 Calvary of the High altarpiece at the Cathedral of Palencia , Juan de Valmaseda.

Fig. 2. Our Lady, Calvary of the High Altarpiece at the Cathedral of Palencia, Juan de Valmaseda.

Fig.3 Saint John, High altarpiece of the Cathedral of Palencia, Juan de Valmaseda.

Fig. 4 The Christ between angels, Diego de Siloé. Altar-piece of Saint Ana, Cathedral of Burgos

Fig. 5. Pietá, Iglesia de Santiago de la Puebla, Salamanca, Diego de Siloé or Juan de Valmaseda.

Fig. 6. Altarpiece of the "capillla de San Ildefonso ", Cathedral of Palencia, Juan de Valmaseda.

Fig. 7 Relief representing the Wise Kings , Capilla de San Ildefonso, Cathedral of Palencia, Juan de Valmaseda.

Fig. 8. San Sebastian from the Rodriguez Acosta Collection, Juan de Valmaseda

Fig. 9. Allegorical figure representing Death. Juan de Valmaseda, Museo Nacional de Escultura de Valladolid

Fig. 10 Saint Jerome , “Capilla del Condestable”, Cathedral of Burgos, Diego de Siloé.

Fig. 11 Saint Jerome, Alonso Berruguete, Museo Nacional de Escultura de Valladolid.